A Palimpsest of Code

I don’t know enough to assert one way or another whether the Google Books ruling is ultimately a “good” or a “bad” decision. What I do know is that it is fascinating.

US District Judge Denny Chin’s decision is, to my mind, far more interesting than a legal ruling has any right to be. I say this because at the core of the legal decision is a mind-twisting idea:

The display of snippets of text for search is similar to the display of thumbnail images of photographs for search or small images of concert posters for reference to past events, as the snippets help users locate books and determine whether they may be of interest. Google Books thus uses words for a different purpose — it uses snippets of text to act as pointers directing users to a broad selection of books.

…Similarly, Google Books is also transformative in the sense that it has transformed book text into data for purposes of substantive research, including data mining and text mining in new areas, thereby opening up new fields of research. Words in books are being used in a way they have not been used before. Google Books has created something new in the use of book the frequency of words and trends in their usage provide substantive information.

Google Books does not supersede or supplant books because it is not a tool to be used to read book. Instead, it “adds value to the original” and allows for “the creation of new information, new aesthetics, new insights and understandings.” Hence, the use is transformative.

Think about that: turning text, already one form of “data”, into another form of data is “highly transformative”. It’s a translation of sorts, but if translation is a kind of chemical reaction, then the source material here is both reactant and catalyst, the thing being changed and the thing left untouched.

It’s as if on a printed page you have letters and words functioning one way, and then underneath it, as a kind of a trace, is an entirely separate code system that contains meaning temporarily invisible to the reader. It’s a palimpsest of code!

Now, here’s what I’m wondering: What are the narrative possibilities of a text that is always operating in two, mutually incompatible but still comprehensible languages — as if a printed page or a section of text always has hovering just above or below a holographic page of code? What might a book look like or do if it put itself forth in two distinct ways, as always both prose and programming language, narrative and the database?

In a sense, we have something like an analogous precedent. You could, if you wanted to, read Ulysses utterly unaware of the sprawling network of references, focusing on the ostensible narrative. “Underneath” — or perhaps more accurately, alongside — is another sign system of meaning, working its way “invisibly” through the text. Diving into that set of code opens and up and eluciates the text in no end of rich, meaningful ways, situating the novel in both its aesthetic and ideological context.

Can we do that with code? What I do not mean is an executable hidden in the margins, opening up a game or a movie about the book. Instead I’m talking about bits of meaning, marked out in inconspicuous ways that only reveal themselves if the interpreter approaches them in the right “language” — patterns, repetitions, cadences, or rhythms, only readable by the machine but full of human possibility.

Imagine a novel about a musician that reveals its off-kilter time signature through measured instances of the word “beat”, or a text about the immigrant experience that ran unseen contradictory interpretations of key moments backwards through a narrative.

Have we been going at the connections between literature and code all wrong? Should we instead be focusing on an interrelationship between the two that is as constitutive as it is invisible, unreadable?

snark vs. Snark

Those of us who have been following Snarkmarket for a long time often bond over the common experience of having to explain to friends and newcomers that despite our gleeful habit 1 of using Snark as a prefix for everything Snarkmarket (Snarkmatrix, Snarkmarketeers, Snarketeers, Snarkives, Snarkserpent, Snarkicon, Snarkseminar, Snarkfriends) Snarkmarket is not very snarky at all. In fact, it’s kind of the opposite of snarky. But what does that mean? 2 Read more…

Notes:

- Really, the very presence and flavor of glee in this habit almost proves how unsnarky we are. ↩

- If you think this post is too long, and it probably is, just take a look at the Venn diagram I made and check out the PSD file and make/annotate your own. ↩

“Give me a hand…”

I don’t have the time anymore to sink into playing million-dollar blockbuster videogames, but occasionally I’ll watch other people play, as recorded on YouTube. It’s fascinating to see and hear people reacting to things happening onscreen. The closest thing that we had to this before the Internet were DVD-commentary-tracks, and while those have an appealing sense of authority and finality in a director-driven industry, player-commentary Youtube videos are actually perfect for games. What better way to represent games as systems, where all kinds of things can happen depending on what players do, than having hundreds of videos by players taking hundreds of different paths?

This morning I watched James Howell’s multi-part commentary on The Last of Us:

The Last of Us is by Naughty Dog, known for crafting expensive, well-written games that are as fun to watch as they are to play. (Their previous games include a trilogy of treasure-hunting adventures that feel like extended Indiana-Jones movies.) Unlike their earlier work, though, The Last of Us is set in a post-apocalpytic world with zombies, and notably focuses on cooperating with characters the player gets stuck with. This means moving through levels and solving puzzles together, boosting each other up to high ledges, and carrying around planks of wood to span wide gaps.

It’s not particularly ground-breaking or challenging as gameplay, but James argues that these basic actions are used over and over again as a vocabulary for talking about trust. Over the course of the game, the main character Joel has to work with a cast of characters, who he (dis)trusts on varying levels – and it’s expressed in gameplay as he lets some help him and tells others to just stay put.

There’s a whole set of variations, though – it foreshadows betrayal when someone accidentally drops Joel while pulling him up to a ledge, it shows distance and tension when characters forget to boost each other up, and when an initially distrustful pair begins to show cohesion and teamwork as they open gates together and fend off zombie attacks off one another, it’s a glorious feeling.

Characterization by systems! Storytelling in interactivity! There’s so much space to explore here.

Having a vocabulary to explore this in all its subtleties is amazing for another reason, too – I point to Tim’s post about journalism dynamics as Batman vs the Justice League – because many of us don’t know how to talk about freelancing on our own, or being part of a loose collective or even an institution. What does dysfunction feel like? How can you recognize it? It’s hard to spot the warning signs unless you’ve gone through it (and have the battle scars to match). But in these systems of interactivity, between the zombies and the shooting, are safe zones from which to look at and play with this stuff.

Chronic traumatic masculinity / Tim

Brian Phillips has written a terrific essay for Grantland on the culture of ritualized pain and intimidation in football, and the ways that sports fans share, enable, embrace, and vicariously live out fantasies through it. It’s called “Man Up: Declaring a war on warrior culture in the wake of the Miami Dolphins bullying scandal.”

I love football — it’s so much fun, it’s beautiful, it’s thrilling, it’s an excuse to drunk-tweet in the mid-afternoon — but it has also become the major theater of American masculine crackup. It’s as if we’re a nation of gentle accountants and customer-service reps who’ve retained this one venue where we can air-guitar the berserk discourse of a warrior race. We’re Klingons, but only on Sundays. The Marines have a strict anti-hazing policy, but we need our fantasy warrior-avatars to be unrestrained and indestructible. We demand that they comply with an increasingly shrill and dehumanizing value set that we communicate by yelling PLAY THROUGH PAIN and THAT GUY IS A SOLDIER and THE TRENCHES and GO TO WAR WITH THESE GUYS and NEVER BACK DOWN. We love coaches who never sleep, stars who live to win, transition graphics that take out the electrical grid in Kandahar. We love pregame flyovers that culminate in actual airstrikes.

And of course this affects the players. Locker-room guy-culture is one thing; the idea that any form of perceived vulnerability is a Marxist shadow plot is something else. It’s a human inevitability that when you assemble a group of hypercompetitive young men some of them will go too far, or will get off on torturing the others — which is why it’s maybe a good idea, cf. the real-life military, to have a system in place to keep this in check. What we have instead is a cynical set of institutional fetishes that rewards unhealthy behavior. The same 110-percent-never-give-an-inch rhetoric that makes concussed players feign health on game day encourages hazing creep after practice. Don’t believe that? I’ve got a helmet-to-helmet hit here for you, and that’ll be $15,000, petunia.

This of course reminds me of David Foster Wallace’s amazing essay on pro tennis, “The String Theory” (which I riffed on with respect to broader athlete culture during a guest stint at Kottke.)

But it also resonated with this story Adam Rothstein pointed me to today, about the culture of police officers and police encounters. It’s called “An Ex-Cop’s Guide To Not Getting Arrested.“

Every interaction with a police officer entails two contests: One for “psychological dominance” and one for “custody of your body.” Carson advises giving in on the first contest in order to win the second. Is that belittling? Of course. “Being questioned by police is insulting,” Carson writes. “It is, however, less insulting than being arrested. What I’m advising you to do when questioned by police is pocket the insult. This is difficult and emotionally painful.”

Make eye contact, but don’t smile. “Cops don’t like smiles.” Winning the psychological battle requires you to be honest with cops, polite, respectful, and resistant to incitement. “If cops lean into your space and blast you with coffee-and-stale-donut breath, ignore it,” Carson writes. Same goes for if they poke you in the chest or use racial slurs. “If you react, you’ll get busted.” Make eye contact, but don’t smile. “Cops don’t like smiles.” Always tell the truth. “Lying is complicated, telling the truth is simple.”

He also says you should be dignified — unless it looks like you’re about to lose both the psychological contest and the one for custody of your body. In which case, you should be strategically pitiful.

I want to be clear — this is insane. This is all some real PTSD shit. These are mechanisms that make a bit of strategic sense in dealing with an abusive parent, or surviving in the Jim Crow South. They are not and must not be tools for dealing with civil servants upholding law and order, in playing a game, or dealing with your colleagues in the workplace. (Always remember, pro sports are both of the latter.)

I mean, maybe we are all suffering with a form of PTSD, after centuries of patriarchy, racial violence, labor violence, and warfare whose legitimacy suddenly (from the long view of eternity) seems suspect. And if PTSD is the wrong acronym, let’s borrow the new term of art football has made famous. What we have is chronic traumatic masculinity syndrome.

Just like NFL players suffer long-term brain damage from both hitting with and suffering damage to their heads, we as a culture are suffering from long-term damage both from and to an parodic and extremely pathological image of masculinity.

As it’s being chased out of places where it used to be welcomed — the household, the workplace, even the military — this strain of CTM pops up in a concentrated form, like antibiotic-resistant bacteria, in a handful of spaces. Pro sports. The police. Wall Street. Rap music. Reddit threads. (NB: I like all of these things, at least MINUS the bullshit masculinity people feel the need to display there.)

It’s a toxic expression of our long-toxic history, that not only subjects, objectifies, and physically and emotionally abuses women, but stops seeing men as people with feelings, with internal organs other than the ones they use to hit each other, but as generators of violence, and statistics.

“Law enforcement officers now are part of the revenue gathering system,” Carson tells me in a phone interview. “The ranks of cops are young and competitive, they’re in competition with one another and intra-departmentally. It becomes a game. Policing isn’t about keeping streets safe, it’s about statistical success. The question for them is, Who can put the most people in jail?”

CTM has no easy solutions or easy cure. But just like in football, the activism will have to start from within. And we’d better find a way to get real with the story, pronto.

The structure of journalism today / Tim

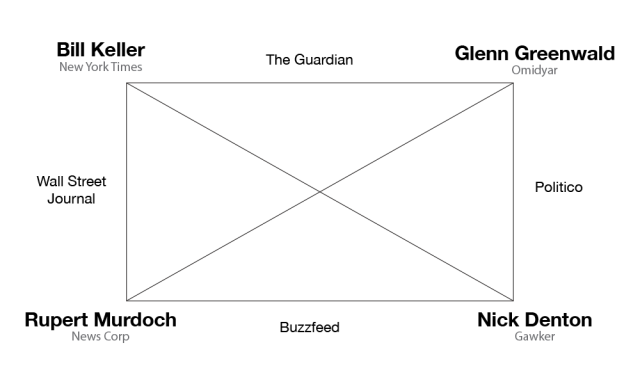

I played a funny litcrit game with a very serious journalism debate. I started drawing lines and rectangles and filling in blanks. It’s a little like highbrow madlibs. And it helped me figure a few things out.

Short summary: the debate between Glenn Greenwald and Bill Keller in the pages of the NYT articulates a lot of the big ideas people inside and outside the profession have had about the practice of journalism. (Also, about the relative merit of David Brooks, but that’s a sideline.)

But by framing it as a back and forth between two poles, it leaves a lot out. It actually doesn’t really recognize how close Greenwald and Keller really are in their basic assumptions about what kind of journalism is important and why, in their faith in the truth and in reader’s abilities to sort out really hard questions for themselves. And they’re arguing with each other, but also past each other, to targets they can’t quite bring themselves to name: people like Rupert Murdoch, and Nick Denton.

The left side is corporate or traditional media; the right is online media. The top is “serious” journalism; the bottom is tabloid journalism. For Keller and Greenwald, journalism is a calling; for Murdoch and Denton, it is a business. And without the largesse of patrons committed to the same ideals of journalism, the New York Times and Greenwald’s untitled venture with Omidyar would be very paltry businesses indeed, while Denton’s and Murdoch’s flourish, grow, and evolve. The New York Times, Washington Post, Guardian, and Pro Publica, and a few others, have found a space in which they can continue to exist. But it seems to me foolish to deny that for everyone else, the business models and journalistic practices mapped by Murdoch and Denton are proving to be much more robust, repeatable, and influential.

The picture up top is called a semiotic square, and it’s a way of representing a few basic principles:

- Most attempts to think through things rest on an opposition between two ideas;

- When you pick those two, you’re usually suppressing two other oppositions;

- You’re also usually suppressing some kind of excluded middle or reconciliation between opposed terms.

This has always felt very logical to me. Maybe it’s because it’s like a math problem. If we say, “ok, there are two kinds of numbers, whole numbers and fractions” — well, you’re forgetting about the things that are neither of those. And that’s actually MOST of the numbers. So we say, okay, there are whole numbers and fractions, and not-whole numbers, and not-fractions (irrationals). But wait — now we’re just talking about REAL numbers, and if we’re interested in NUMBERS, you’ve got to talk about imaginary numbers too. And not just imaginary but complex.

And so on. You can always, always, ALWAYS, go further down by expanding and relaxing your field of assumptions. And you can do it all with a pen and a piece of paper. (For reasons I don’t fully understand, this has always been really important for all the fields I’ve been drawn too intellectually — the only tools you need to carry them out are books, pen, and paper. Maybe a calculator, ruler and compass, and a camera.)

But because I know you can always go further down, I know that this graph of journalism is really incomplete. It’s a schema — it clarifies some things, but it obscures even more. And it makes things fixed that are really on the move. It’s like those beads-and-wire atomic models we made of elements in middle school — shit, electrons just aren’t moving around in quiet circles like that. Electrons are a MESS.

So I’d really like to get some pushback and extensions on this here. Jay Rosen was kind enough on Twitter to say that I didn’t pay enough attention to the debate over insiders vs outsiders, access vs accountability, in contemporary journalism. I talk about it a little bit in terms of complicity with the mechanisms of power. But how extensible is that to finance journalism, sports, entertainment, technology? Maybe it is, or maybe we need to blend that discussion with one of access.

And that points to another limitation: even the graph I made sort of takes investigative political journalism as being the field of discourse. And news, journalism, media is enormous! And the centrality of political accountability journalism is not at all self-evident.

Does Silicon Valley care about this shit? Does Wall Street? Does the science blogosphere? Does ESPN? Kinda. But not really. For them the field of action, of real power, of news of genuine importance, is elsewhere. It intersects with that world of electoral politics and state power, but only tangentially and accidentally.

And where do data and coding fit in? Nothing in this graph tells me whether I should learn to code, or what “learning to code” means. Which as we all know, is the most important question for journalism in human history. I mean, if I knew how to program in R, this sad-ass square could be a super-slick data visualization with crazy mouseovers and tilt-shift views and shit.

So what do you all think? If this is a place to start, how can we make it better?

“Liking” poems / Jay

It’s taken me some effort to learn how to appreciate poetry. I can make broad statements about liking books and music without having to like all books or all music, but with poetry–for whatever reason–it’s been more difficult.

However, as someone who would also say he likes math, opening a book of poems and seeing this has immediate appeal:

This is from R. D. Liang’s Knots, a book of poems about “the patterns of human bondage.” I like this. It gives me that “this looks crazy and I want to understand it” feeling.

That feeling is everywhere in math, though it has nothing to do with liking numbers or concepts: It’s a love for the notation itself, the joy of getting to move towards increasingly strange symbology as you understand more.

And reading Knots feels much the same — up to a point. My fascination thus far is wholly with its notation (e.g. the cryptic use of brackets, the strings of random numbers) and the structures in the book itself (e.g. its syntax — the “knots”). Try this one, for example:

Jack sees that

Jill does not know

Jack does not know what

Jill thinks

Jack knows.

But Jack can’t see

why Jill does not know

that Jack does not know

what Jill thinks

he knows.

I’ve been reading these poems for the last few nights and I’ve still yet to get much closer to appreciating the subtleties of what Liang has to say about human psychology. (To me, the poem fragment above is not so much about “knowing what others know” as it is about learning how to parse the sentence to read it.) In some sense, I’m hung up solely on the way it’s presented rather than on what it means.

So I’m curious: When is it okay to not want to understand? (Or is it always okay?) Is “understanding” a poem something different from understanding other things?

Media wisdom / Tim

An observation from Siva Vaidhyanathan:

In Holland, “media literacy” is called “media wisdom.” I love that.

The Dutch word is “Mediawijsheid.” The Dutch sometimes use “media literacy” too, to describe strict literacy, but “media wisdom” has a specific slant, similar to (but I think stronger than) the more robust sense we sometimes give literacy:

In the Netherlands media literacy is often called “media wisdom”, which refers to the skills, attitudes and mentality that citizens and organisations need to be aware, critical and active in a highly mediatised world.

Wisdom. What we really mean, what we have always meant, is wisdom.

Laughing at the game

After having completed developer Quantic Dream’s most recent game Beyond: Two Souls, I felt myself compelled to tweet that the ending had made me laugh out loud.

No, really.

All right, I just laughed out loud at the Beyond: Two Souls ending.

— Gavin Craig (@craiggav) October 29, 2013

Now, like other Quantic Dream games — Heavy Rain, Indigo Prophecy/Fahrenheit — Beyond: Two Souls can pretty fairly be described as a game that is not trying to engender laughter. It’s a serious game about 15 years of its main character’s life in which serious things happen. Like being abandoned by her parents to be raised in a secret lab, and fighting Very Bad People in the Third World, and then discovering that maybe the Very Bad People weren’t who she was told they were. Also, there’s a ghost who follows the main character everywhere. Did I mention the ghost?

There are also big problems with the game. The nonlinear structure of the game’s chapters doesn’t appear to be very well thought out. For a character-driven story, none of the characters are particularly realized. I’ve heard more than one person comment that it appears at times that the writers have never actually had a conversation with another human being. I haven’t even mentioned the “Navajo” chapter, in which the white main character saves a Native American family by recovering the rituals of their people, and, um, yeah.

But for all this, I found myself laughing at the end of the game. Not screaming, not throwing my controller at the TV, laughing. Somewhere, at least for a minute, Beyond: Two Souls had crossed the line separating the ridiculous from the sublime, and that, for me at least, was a striking event.

While videogames are built on over-the-top, excessive worlds, where if one of anything is good, fifty is better, I’ve almost never seen a discussion of a game in terms of camp — Read more…

ALLOW US TO REINTRODUCE OURSELVES / Tim

This is the new Snarkmarket. I want to welcome you inside, and tell you how we got here.

Five years ago today, I joined Robin Sloan and Matt Thompson at Snarkmarket.com, a two-person site they’d built to write about media, the future, and everything else. It was the site’s fifth anniversary. (It was also the day Barack Obama was first elected President of the United States.) For five years, I’d haunted the comments at Snarkmarket, writing responses longer than the posts themselves; now I was being asked to join the show.

It may be a strange thing to wrap our minds around now, but being a member of a popular but noncommercial blog in 2008 was a very big deal. Nobody was getting paid, and nobody was doing what was recognized as “work,” but it was a platform that brought two things with it:

- Writing for the best, smartest, most playful community of commenters on the internet;

- Access to the wider Snarkmatrix, the readers who’d followed the blog from the start, back before there had been so very many of us, and many of whom had fallen upwards to positions of influence and responsibility.

Snarkmarket gave me a fighting chance of writing about something besides university books for a university audience. I felt like I’d won a lottery ticket. And for the next two years, that kicked off my favorite period in the history of the site: when we made New Liberal Arts, when Robin improbably became a bestselling novelist, when Matt returned from the midwest to help reinvent blogging for NPR, when I even more improbably became a technology journalist at Wired and then The Verge.

But as the three of us were pulled into our thirties, and that decade’s corresponding commitments, and as much of the discussion around news and ideas began to shift away from user-owned blogs to new media properties and superheating social networks, Snarkmarket entered a new phase. During this time, Robin called Snarkmarket “a hardy desert ecosystem.” The site proved infinitely adaptable, but its visible flourishing diminished.

As we approached our tenth anniversary, Matt and Robin and I had an idea. We would make the Snarkmatrix — our community of readers, commenters, friends, well-wishers, lurkers, and musers — manifest. We would assemble at the Poynter Institute, where it all began, as Matt and Robin decided to start a blog. We would celebrate Snarkmarket’s tenth birthday with the people who’d made it possible.

But — and this is where the hardy desert ecosystem metaphor becomes especially useful — we also took the Snarkmatrix underground. We started doing weekly meetings — a Snarkseminar — where different members would bring to the group ideas, problems, texts, videos, questions for the group to discuss and respond to. The whole thing was Powered By Google; we’d doodle on a Google Doc each week with marginal notes, conduct a live hangout. Whoever could come was welcome; if you couldn’t make it, no harm, no foul. And it was exciting to see what we could do with those tools, in that smaller space, with two or three dozen people actively collaborating on an idea rather than two or three guys (however skilled we three might be).

And for a while, we thought that would be where it would end. A victory lap for the community we brought together, a reward to people who’d found us, whenever or however they found us. And a reward for the three of us, a big party in Florida with our best friends and biggest fans.

We thought we’d get a little Kindle single out of it — here are the products of our labors, a set of final projects for the Snarkseminar, created by the community online, hammered out face-to-face. And that was exciting.

But then we thought: what if we go bigger?

What if the point of the tenth anniversary of Snarkmarket wasn’t to present its tombstone, but to bring it back to life, bigger and stronger and bolder than ever? And what if the mechanism for its resurrection was right in front of us — the core community of Snarkmarket readers and commenters, to many of whom the site (and the ideas animating the site) meant as much as it did to us?

What if the tools we needed to create a fun, participatory, community-driven blog were available to us, and what if this time, right now — the age of social media, the age of the new, big-business online media company, driven by ads and scale and Hadoop nodes and dataviz and all that marvelous crap — was to double the fuck down on the enthusiast, curated, small-n multiuser blog? What if it was time to go full

So that’s what we’re doing. Five years ago, Snarkmarket went from two editors to three. Now our community is growing by dozens. You’re going to see a lot of new writers here — but if you’ve been a long-time reader, they won’t be strangers. You’ve been seeing them in the comments for years.

We’re also building new tools and interfaces to try to take advantage of this newfound swarm of talent. We’re going to have collaborative stories, inline glosses, conversational forks. We’re going to try to reimagine (with the robust tools we already have, tweaked by some of our design geniuses) what a group blog looks like, and what it can do for the reader.

And that’s just the beginning. If we do this right, is a collective that will be continually throwing off new objects like sparks from a hammer on hot steel. Some of those will be objects you can participate in making. But for now we’re settling in, seeing what this new Snarkmarket can do.

There’s been a lot of discussion in the last few months as new sites have launched, also trying to do new experiments in online writing and reading in 2013. “Is ______ a platform or a media company?” is the new “Are bloggers journalists?”

Snarkmarket is proudly neither a platform nor a media company. It is a community of friends and colleagues, allies and advocates, learners and thinkers, who have gathered together for mutual aid, support, and encouragement, and experimentation. The visible expression of that community is now, as it has been, what you see at Snarkmarket.com. We want you to join us as a commenter. We want you to cheer us on. We want to cheer you on. We want to know what you think. We’re ready to try anything. We’re ready to see what’s possible.

Let’s light this candle.

Paper and ink, pixels and Flash / Tim

Today, it’s not just the government that’s back in business! The internet gives us two great articles about cartooning (and technology!) that go great together.

First, Mental Floss scored a huge coup and interviewed the elusive/reclusive/exclusive Bill Watterson, author and artist of Calvin and Hobbes. (As I said on Twitter, this is like ten Salingers times a Pynchon.)

Where do you think the comic strip fits in today’s culture?

Personally, I like paper and ink better than glowing pixels, but to each his own. Obviously the role of comics is changing very fast. On the one hand, I don’t think comics have ever been more widely accepted or taken as seriously as they are now. On the other hand, the mass media is disintegrating, and audiences are atomizing. I suspect comics will have less widespread cultural impact and make a lot less money. I’m old enough to find all this unsettling, but the world moves on. All the new media will inevitably change the look, function, and maybe even the purpose of comics, but comics are vibrant and versatile, so I think they’ll continue to find relevance one way or another. But they definitely won’t be the same as what I grew up with.

Cue up Onion A/V Club’s Todd van der Werff, who looks back at that other great grandchild of Charles Schultz’s Peanuts, Mike and Matt Chapman’s pioneering web video series Homestar Runner.

Much of Homestar Runner’s animation is fairly rudimentary stuff. Arms go up and down. Mouths flap open. Characters stand in place while the background races past them to indicate movement. But all of that belies the program’s true strength: terrifically designed, perfectly written characters. The weirdos that populate Homestar’s world aren’t drawn from animated kids’ shows or even children’s books, but from another great American art form: the newspaper comic strip. As with Peanuts or Pogo, the characters may have hidden depths, but they’re largely defined by striking, singular personality traits. Homestar is the good guy, and even if he’s a bit of a nerd in the process, he’ll always return to that basic decency. Strong Bad proved too slippery for the antagonist role and ended up becoming something like a 10-year-old boy’s conception of everything that is awesome in the world. His brothers, Strong Mad and Strong Sad, were just what they sounded like. Coach Z was motivational, in his own weird way. The Cheat was basically Snoopy.