As you already know by now from Robin and Tim’s posts, DC comics is relaunching the continuity of its primary universe. While I’ll admit that my first reaction as a current collector of a handful of DC titles (Batman, Detective, Red Robin, Batgirl, Batwoman if it ever comes out, and anything with The Question—I’m new here, I have to establish my bona fides), is to geek out over all the details.

Barbara Gordon will be Batgirl again (and even better , written by Gail Simone)! Tim Drake loses his own title, but gets a new costume! Superman won’t be wearing red underwear over his tights anymore! Wonder Woman is keeping the pants! Other details, I’m sure!

Barbara Gordon will be Batgirl again (and even better , written by Gail Simone)! Tim Drake loses his own title, but gets a new costume! Superman won’t be wearing red underwear over his tights anymore! Wonder Woman is keeping the pants! Other details, I’m sure!

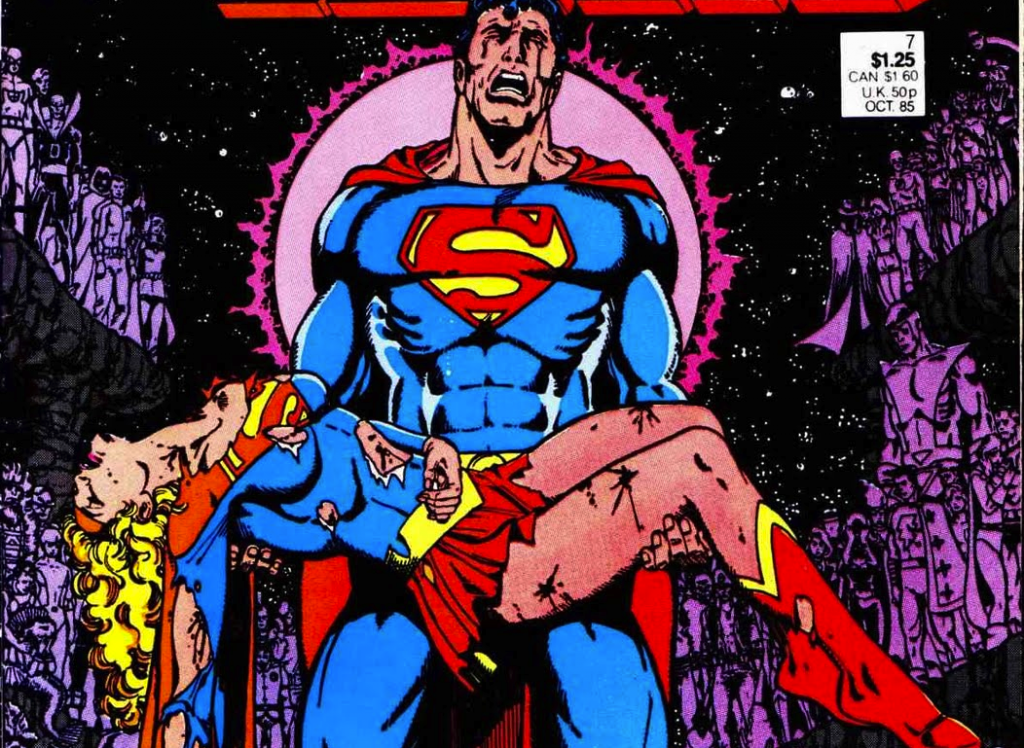

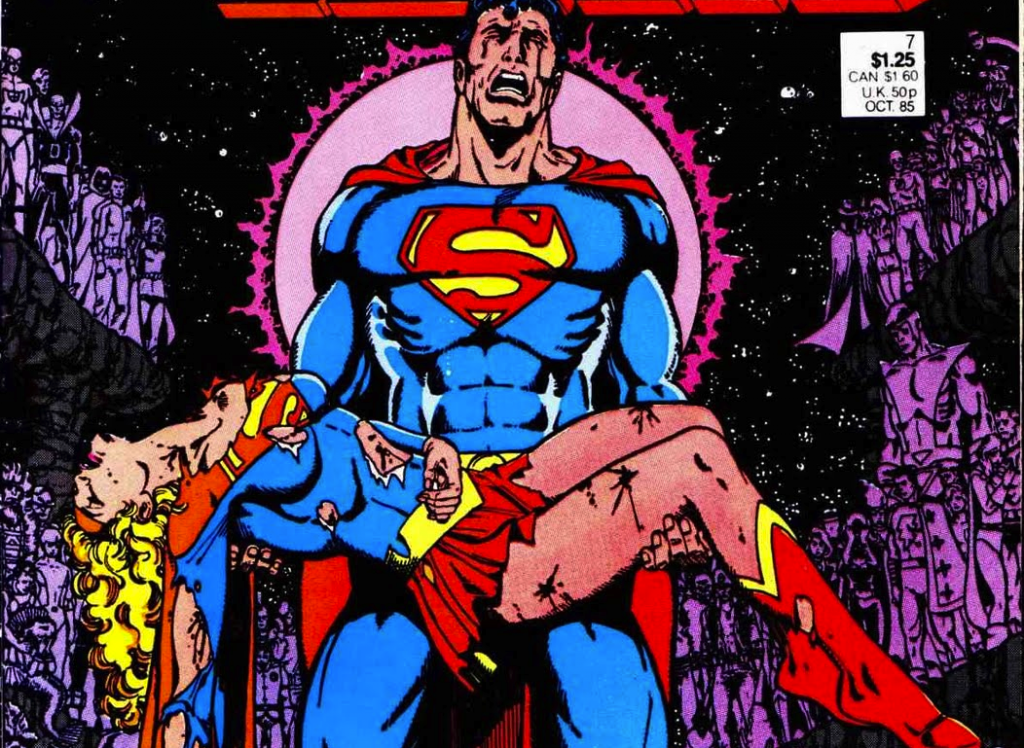

And before I try to make a bigger argument, let’s all focus on the fact that the details are all that really matter here. This isn’t the first time that DC has rebooted its continuity. 1985’s Crisis on Infinite Earths was arguably DC’s first attempt to bring all of its titles together into a common, consistent universe. Zero Hour followed in 1994, and Infinite Crisis in 2005.

There have been other big crossover storylines like Armageddon: 2001, Identity Crisis, Final Crisis, and Blackest Night, but while these storylines have had greater or smaller impacts of the status quo, they didn’t, for the most part, erase most or all of established storyline history.

In this light what’s really notable is that A.) we’re ahead of schedule (the next reboot shouldn’t be until 2014 or 2015), and B.) all title numbers are being reset to #1.

Which is, of course, a marketing ploy. Industry wisdom is that #1s sell better. If DC’s marketing department had their wish, every issue would be #1, every month. A world of one-shots! Every issue a collector’s item!

But all of this still misses what’s really interesting about the relaunch, and every Elseworlds title, every Crisis, every Age of Apocalypse, House of M, Ultimatum, and on, and on, and on.

Continuity is a storytelling technology. It’s a way of organizing information, conveying character over extended periods of time, giving depth to plot, and communicating history in a way that doesn’t demand retelling with each iteration.

It’s an enormously useful tool, with rewards for both writer and reader, but it also has limitations. It highlights any asymmetry in knowledge between writer and reader. If the story you’re reading demands familiarity with a previous story you missed, you can feel lost. If the writer contradicts a previous story, you can feel that something is wrong. In a medium, like superhero comics, where the suspension of disbelief is critical, a discontinuity can be fatal.

Or not. As the DC Universe in particular illustrates, continuity is nothing if not elastic. Between 1938 and 1985, it wasn’t even seen as particularly necessary. Each corner of the DC Universe largely concerned itself with its own particular space, and, in practice if not editorial principle, that’s largely true today as well. In fact, I’d argue that every new story recreates its own continuity. That is, this big thing that we’re spending all our time worrying about, hyping, ruing the lost of, it doesn’t really exist. Every writer constantly has to decide what to use, what to ignore, and what to re-invent. There’s even a word for changing continuity on the fly— retcon, for “retroactive continuity,” which is now both a noun and a verb.

Robin makes an excellent point that continuity, this depth of character and wealth of story, is the one major attraction that the big comic companies still hold for creators — and that if you have a lottery-ticket idea, the character and story that will be the next Batman, or Harry Potter, or Twilight, then you’d be a fool to sell it to Marvel or DC like Bob Kane, Jerry Siegel, and Joe Shuster did back in the 1930s. It would probably be more accurate to view Marvel and DC as they currently exist not as comic book companies, but intellectual property holding corporations that happen to print a handful of comic books, as just one way in which they manage and profit from their IP. I guarantee you that at the top levels, it’s how they view themselves. They have to.

But at the same time, it’s not really an either-or position. Jim Lee, one of the founding forces behind Image Comics — who may not have created creator-owned comics, but gave the proposition market power like few entities before — is also one of the driving forces behind the DC relaunch, which will introduce a number of his former Image franchises such as Grifter and Stormwatch into DC continuity.

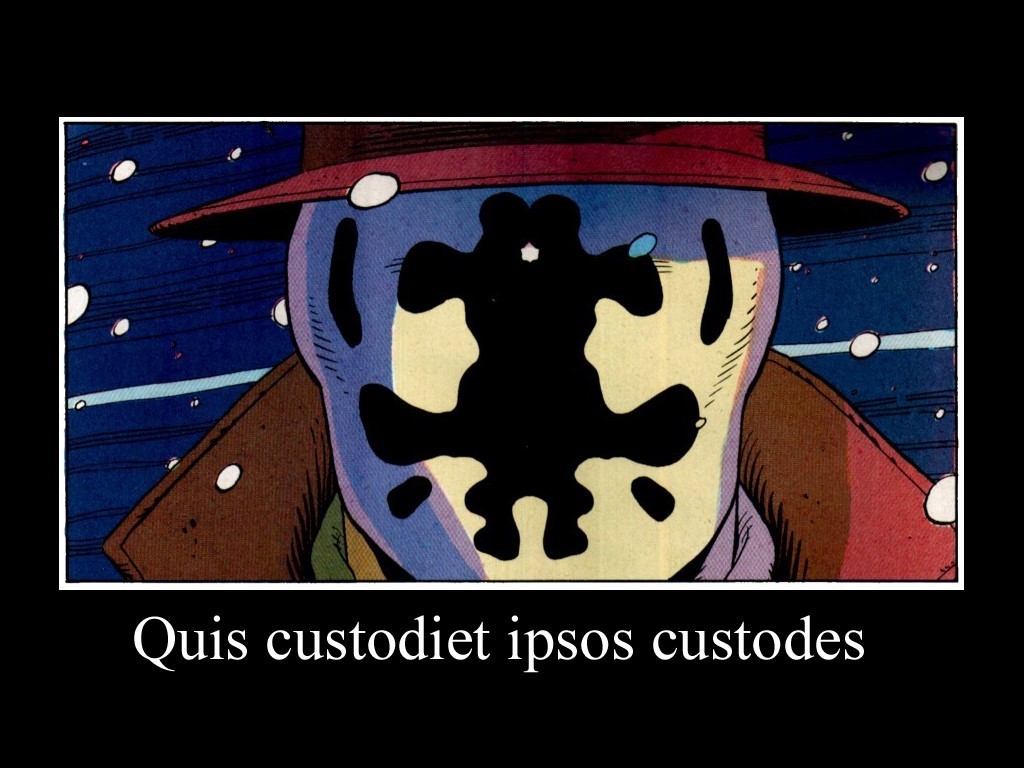

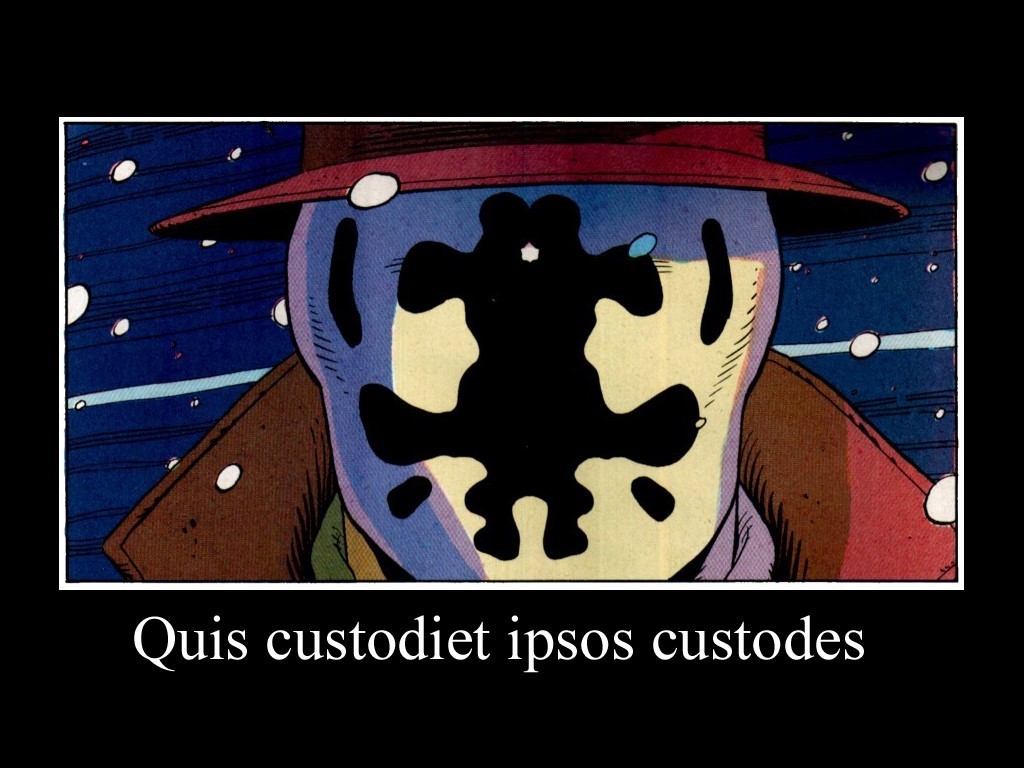

This, of course, isn’t the first time that DC has integrated other universes into its own. Captain Marvel was originally a property competing with (and more popular) than Superman, until DC sued, shut down publication, and eventually acquired the character. Alan Moore’s groundbreaking Watchmen comic originally grew out of DC’s acquisition of Charleton Comics’ characters, but since Moore’s storyline made many of the characters, um, unusable, DC made him create new ones. (Captain Atom became Dr. Manhattan, The Question became Rorschach, etc.)

By rebooting its continuity, DC is, in effect, updating its operating system. We’ll know in a few months whether it’s Linux or Vista.

But rather than thinking of continuity as some sort of sacred history of tradition, let’s remember that it’s a technology. And like any technology, it might be most interesting once we start thinking about how it can be hacked.

The canonical example of a continuity hack may be Watchmen — but I’d also throw in Grant Morrison’s All-Star Superman, Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns, and Steven T. Seagle’s It’s a Bird. All of these stories play with continuity, not in order to retcon, reboot, or reinforce it, but to use that root access for their own idiosyncratic purposes. And it’s these interventions, not the big events, that ultimately bring the stories back to their foundations and move the whole industry forward.

Barbara Gordon will be Batgirl again (and even better , written by Gail Simone)! Tim Drake loses his own title, but gets a new costume! Superman won’t be wearing red underwear over his tights anymore! Wonder Woman is keeping the pants! Other details, I’m sure!

Barbara Gordon will be Batgirl again (and even better , written by Gail Simone)! Tim Drake loses his own title, but gets a new costume! Superman won’t be wearing red underwear over his tights anymore! Wonder Woman is keeping the pants! Other details, I’m sure!