The Three-Year Degree / Tim

When I read this:

At most European universities, students receive their undergraduate degrees in three years – and Graduate School of Education professor Robert Zemsky thinks American should do the same…

First, he argues that because the majority of students now pursue advanced degrees, it is logical to find ways to shorten the time they spend in college in order to get a jump-start on professional and graduate degrees.

Second, Zemsky says in order to help American students transition to a three-year undergraduate system, their senior year of high school could be focused on developing the skills students will need to keep up with the accelerated pace.

I thought, don’t we do this already, by having most undergraduates (at least at relatively elite schools) take a year or semester abroad? Then Chris Shea backed me up:

Some American colleges–Yale, for example–used to be so presumptuous as to say that students would be better off spending all four years on the campus. The argument was that courses in the U.S. were more rigorous than most of those that students could find abroad. Want to see the world? Take a grand tour after college.

You don’t hear such arguments anymore. To study abroad is an expected, and seldom-challenged, part of the American college experience.

Writing in the Chronicle of Higher Education, however [subscribers only], John F. Burness, a visiting policy professor at Duke, says there’s more than a grain of truth to the old-fashioned view. The courses students take in study-abroad programs are often weaker than the ones they take at home. And too many students, he says, treat study-abroad programs as an extended opportunity to travel, with coursework, at best, a bonus.

Now travel is nice and all (and, to be sure, the best study-abroad programs are simultaneously challenging and horizon-expanding). But as one Marshall Scholar, a serious recent graduate, tells Burness: “For many students, study abroad is a semester off, not a semester on.”

So, the real problem seems to be that many university undergraduates really DO have a three-year college education; but that many of them are wasting their time in Europe rather than applying to graduate schools before they turn twenty-one.

The logic in both counterarguments is all about efficiency, acceleration – and implicitly, that a student should be finished with their education sometime between 21 and 25.

I will be the first to admit that is a terrible, terrible thing – really, a kind of disease – to be a twenty-nine-year-old graduate student. (Being a thirty-year-old postdoctoral fellow is a little like being in remission.) But I don’t think that hurrying the entire process along is a) where we are headed or b) where we want to head.

On the other hand, if you wanted to promote a three-year baccalaureate on the grounds that it would be easier for adults to finish their education and retrain themselves for new positions — I think I’d be a lot more sympathetic to that.

The Op-Tech genre of journalism, Pt. 2 / Tim

More thoughts on Op-Tech writing at major dailies. In particular, I had a sentence that I wanted to squeeze in, but forgot about until an hour after I hit submit: “Op-Tech is equal parts business, politics, and aesthetics.”

Think about it! Most of this journalism is about major corporations who each release a handful of significant products or technologies each year. In a few cases, a Pogue or Mossberg will spotlight peripheral objects by smaller companies. But it’s really about major trends and players in the tech sector, trying to understand and evaluate what’s happening. That’s the business end.

But again, Op-Tech writers don’t largely touch on issues of manufacturing, personnel, law, everything the tech reporters do. They write as users (albeit expert users) for users. They talk about the aesthetics and experience of using an object, and make recommendations to users (and only occasionally to companies) about how best to use and whether to purchase a business or service. This is where they’re closest to food or movie reviewers.

Think about it! Like a meal or a movie, personal digital technology is criticized primarily according to the aesthetic experience of the user. I’ll ramp that up beyond the bounds of plausibility. New gadgets or software packs are among our most important aesthetic objects, more significant and universal than books, TV shows, or movies – so much so that the paper of record requires experts to weigh in on their value and importance.

At the same time, technology writing is political in a way that most aesthetic criticism simply isn’t. What I mean is that 1) there are real arguments between partisans, and 2) these arguments have significant real-world consequences — in ways that criticism of movies or restaurants, simply don’t, unless you live in the right part of Manhattan.

This, I think, is why so many people get upset about the cozy relationship between Op-Tech columnists and the companies they cover – they feel as though criticism, any criticism that might question the strategies of the Major Powers (yes, I’m talking about Apple, Microsoft, and Google as if they were empires on the verge of World War I), is shut out or at least diminished and contained for that reason. The weird position of the major guys as reviewers/insiders/brands appears to guarantee that.

My response would be 1) that you don’t need or even want a David Pogue or Walt Mossberg to be running around playing Edward R. Murrow, and 2) that job is open – at least that sliver that hasn’t largely been filled by magazine writers, academic critics, and independent bloggers.

Still, I would love to see more writing in newspapers that really focuses on the aesthetics of tech – Virginia Heffernan is really the model here – or the broader ramifications of tech policy. Imagine if the New York Times had an opinion columnist – right next to Krugman, Dowd, Brooks, and the rest – writing about the intersection of technology, politics, and culture? Not in Slate, not in the Chronicle of Higher Education – but smack in the middle of the NYT, WSJ, or the Post.

After all, EVERYONE who reads the editorial page of the Times has an opinion about who OUGHT to be writing for the editorial page of the Times.

I say, let’s treat this like it were actually already happening: write your model nominees in the comments below.

The Op-Tech genre of journalism / Tim

David Pogue’s position is that he’s not a technology reporter, but an opinion columnist who writes about technology:

“Since when have I ever billed myself as a journalist?” Pogue said angrily. “Since when have I ever billed myself as a journalist?….I am not a reporter. I’ve never been to journalism school. I don’t know what it means to bury the lede. Okay I do know what it means. I am not a reporter. I’ve been an opinion columnist my entire career…..I try to entertain and inform.”

Recognizing perhaps that the distinction may be lost on his journalist colleagues at the NYT and elsewhere, Pogue added: “By the way I’m suddenly realizing this is all just making it all worse for myself. The haters are going to hate David Pogue even more now.”

This actually becomes a pretty complicated issue when you think about it. On the one hand – and maybe this is a bad example – the NYT hires columnists like Bill Kristol, who’s basic qualification is that they ARE partisans with an interest in promoting one side over an other. Sometimes, like Paul Krugman, they’re really smart, and sometimes like Nick Kristof, they do some reporting. But they’re basically intended to be advocates. You could criticize Kristol for a lot, but it would be stating the all-too-obvious to point out that his professional interest was bound up in the fate of the Republican party. And likewise, it would be stating the all-too-obvious to dig into Tom Friedman’s books and lectures. We’ve essentially decided that it’s cool if political writers are part of the party apparatus and/or ideological institutions. So long as they don’t out-and-out lie, they’re good.

On the other, they have technology and business reporters who are, I don’t know, supposed to uncover true facts about products and companies for consumers or investors or amateurs (like me) who are interested in these things for poorly-defined and even-less-well-understood reasons. Often, though, these reviewers interact with analysis of their objects – if the new Zune might be a hit or a dud, that becomes a fact that potentially affects sales, stock movements, personnel changes… all of that nitty-gritty stuff that’s part and parcel of being a good reporter.

Maybe in the middle somewhere, there are reviewers, usually writers who review books or movies or plays or television shows or restaurants. These writers are expected to be partial but unmotivated – they have an opinion but not a stake. This includes what some reviewers take to be draconian restrictions on reviewing the books of their friends and/or enemies. You’re there for your knowledge and aesthetics – and yet also, paradoxically, you are also there (in part) to sell the media you review.

And essentially, the objects reviewed are aesthetic objects. They’re not ordinary household goods. The closest thing to tech gadgets reviewed in a paper like the NYT is the automotive section, which is grouped with “jobs” and “real estate” in the classifieds. Nobody reviews furniture, or toasters, or bicycles. In a sense, the technology reviewer is the only reviewer who offers an opinion on things you use. At least in a sphere where not just you, but the newspaper itself, has a stake, however small, in selling the object.*

So technology journalism – at least, what I’m calling the “Op-Tech” genre, is somewhere between all of these fields. Like book and movie reviewers, they’re expected to offer their opinion on the aesthetics (and use, too) of objects placed before them. Like reporters, their value lies in their quasi-objective take on a product (which in turn helps move product) and the sources they can marshal to give them access. And like opinion reporters, they’re expected to be entertaining, partisan, and above all personal. After all, it’s their authority, their brand, that creates the conditions under which their opinion is credible (or less often, not).

* This is actually really complicated. One of the most revealing parts of Pogue’s complaint is his claim that he pushed for disclosure of his books in his columns. According to Pogue, his editors resisted it, because they thought it would be seen as self-advertising. “And you know what? I am sorry to tell you guys this, but now that the plug is going to appear in each column it’s going to raise the book sales.” (If you’re an Op-Ed columnist and you write a book, it’ll probably get excerpted in the magazine.)

Quotes from NYTpick.com, via Romenesko.

Humanism at the fringe / Tim

Highly recommended: Janneke Adema’s outstanding extended look at internet text-sharing networks, from relatively high-profile sites like Scribd and UbuWeb to grad-student blogs with a dozen or so lit theory PDFs. (NB: Some of Adema’s early quotations are in untranslated German, but don’t get thrown.)

These sites are tiny and unbelievably idiosyncratic and specialized compared to their DVD-ripping BitTorrent cousins. But if you fit the right niche – especially, improbably, nerds into philosophy and media – you can discover dozens of smart books and articles every day, each lovingly meticulously scanned, OCRed, or hand-typed by a digital scribe.

Small and idiosyncratic is, in this case, part a necessity and partly a strategy:

That there has not been one major platform or aggregation site linking them together and uploading all the texts is logical if we take into account the text sharing history described before and this can thus be seen as a clear tactic: it is fear, fear for what happened to textz.com and fear for the issue of scale and fear of no longer operating at the borders, on the outside or at the fringes. Because a larger scale means they might really get noticed. The idea of secrecy and exclusivity which makes for the idea of the underground is very practically combined with the idea that in this way the texts are available in a multitude of places and can thus not be withdrawn or disappear so easily.

This is the paradox of the underground: staying small means not being noticed (widely), but will mean being able to exist for probably an extended period of time. Becoming (too) big will mean reaching more people and spreading the texts further into society, however it will also probably mean being noticed as a treat, as a ‘network of text-piracy’. The true strategy is to retain this balance of openly dispersed subversivity.

Also instructive: a number of these sites, like AAAARG, are set up as discussion and educational groups. It’s party an issue of – I won’t say legality, let’s say, legitimation. But it’s also about expressing an ethos and giving its users additional tools to make use of the content.

As is stated on their website, AAAARG is a conversation platform, or alternatively, a school, reading group or journal, maintained by Los Angeles artist Sean Dockray. In the true spirit of Critical Theory, its aim is to ‘develop critical discourse outside of an institutional framework’. Or even more beautiful said, it operates in the spaces in between: ‘But rather than thinking of it like a new building, imagine scaffolding that attaches onto existing buildings and creates new architectures between them.’…

The most interesting part though is the ‘extra’ functions the platform offers: after you have made an account, you can make your own collections, aggregations or issues out of the texts in the library or the texts you add. This offers an alternative (thematically ordered) way into the texts archived on the site. You also have the possibility to make comments or start a discussion on the texts. See for instance their elaborate discussion lists. The AAAARG community thus serves both as a sharing and feedback community and in this way operates in a true p2p fashion, in a way like p2p seemed originally intended.

All of the value – ethical, technological, social – is in the scale and interconnectedness of the network. But at a certain point, size actually works against you on all three counts. If I was surer in my astrophysics, I’d call this the solar model of networks.

These communities at their best work to add value to the texts they distribute – through discussion, through juxtaposition, and through the creation of more text. Consider Matthew Battles’s take on Infinite Summer:

Thousands of people have participated in a forum that seems to transcend the idea of the “book club” entirely—the result looks more like a crowdsourced, massively parallel postgraduate seminar. But no, that’s not it either; trappings of institutional learning like “postgraduate” and “seminar” don’t really have a place here. Infinite Jest’s complexity, its author’s pixillated, autodidactic, logorrhoeic condition, make it very hard to teach. But these same qualities, with its flowing, braided links to film, tennis, fractals, logic, and recovery, as well as a score of other topics, make it an enormously productive imaginal space in which to cultivate the kind of wide-ranging, splintering discussion that is native to the web.

And, as Battles points out, these communities of affinity can offer a vitality that can endure whatever might happen to the institutions that gave us those trappings of higher learning in the first place: “I wouldn’t have given you two cents for the institutions at any point in the history of civilization. But the life of the mind isn’t really about institutions, is it?”

Not official institutions, anyways. Just those conglomerations – sometimes accidental – with the right size and composition to become stars.

Pick your POV carefully / Robin

Paul Graham, whose writing I always enjoy, just posted a new piece about publishing and, to a degree, the structure of markets for content. I want to zoom in on one point:

What about iTunes? Doesn’t that show people will pay for content? Well, not really. iTunes is more of a tollbooth than a store. Apple controls the default path onto the iPod. They offer a convenient list of songs, and whenever you choose one they ding your credit card for a small amount, just below the threshold of attention. Basically, iTunes makes money by taxing people, not selling them stuff. You can only do that if you own the channel, and even then you don’t make much from it, because a toll has to be ignorable to work. Once a toll becomes painful, people start to find ways around it, and that’s pretty easy with digital content.

I think this is a cheat—aren’t all stores just tollbooths, then? You never buy goods at cost. There’s a markup, a tax, associated with the aggregation, the curation, the experience. This is as true for a grocery store as it is for iTunes and the App Store. And you can see Graham’s anti-iTunes argument sort of fuzz out as the paragraph proceeds: It starts very specific, then breaks down into a restatement of that old information-wants-to-be-free digital determinism.

But that’s not the point I want to make. Rather, it’s that almost all of this discussion—not just Graham’s, but the broader conversation it’s part of—tends to operate from one of two extreme points of view: either that of the consumer (who wants convenience and economy) or that of the company (which wants big profits, or at least a business model). I find myself wanting—sort of desperately wanting—to hear from a different group: the creators.

And, this is as much of a surprise to me as anybody else, but finding myself more and more in that position—the position of somebody who wants to make content, and make money from that content—I see the Kindle Store and the App Store and I say: thank you.

Now listen, I understand all of the problems. I just got into another round of the iPhone: Is It Evil? conversation last night. (Our conclusion, same as always: yes, a little bit.) But if it’s not yet what we want it to be, at least it moves us in the right direction. In iTunes and the App Store, an individual creator can make something and offer it to the world for a small sum, and people will actually take her up on it. I wish that wasn’t so revolutionary… but it is!

Trust me, I get the argument for free. I love Kevin Kelly’s strategies for selling stuff in the age of command-D. Ransom model, hello?

But at the same time, I don’t want to give up on selling stuff quite yet. I don’t think the central lesson of the App Store is that people will suffer a tax if it’s small enough. Rather, I think it’s that people are happy to pay for things if it’s easy enough. And that’s especially true when those things aren’t the products of Super Amalgamated Content LLC, but rather of Indie Content Haus, or better yet, of your friend Matt.

If that’s true, then Paul Graham’s argument about iTunes leads us in the wrong direction. Digital determinism says it’s a tax, a toll booth, a tortured construct that denies the essential nature of digital content. Pragmatism says—without denying that there’s room for improvement—that it’s a joy, a gift, an opportunity engine.

Now, a question you could ask is this: Why isn’t iTunes proper—the music and video part—more like the App Store? The former is open to indies, but still dominated by big corporate media. The latter is open to big corporations, but dominated (so far) by indies. What’s different? How might you splice some of the App Store’s indie vigor into iTunes proper?

I think one strategy—which doesn’t really answer my question above—is to start thinking hard about how to blur the lines between software and content, and get some “content experience apps” (I promise never to type that again) into the App Store. (Paul Graham ends up saying something similar.) For whatever reason, as a market, it’s working for creators. So maybe it’s simply where creators—of many kinds—ought to go.

Gawande, D-MA / Tim

Faiz Shakir at Think Progress has a pretty stunning proposal: appointing Harvard-based surgeon/author/hero Atul Gawande to Ted Kennedy’s vacated senate seat in Massachusetts.

On the day he would step foot in the Senate, Dr. Gawande would be the most knowledgeable health policy expert in the chamber, an incredible resource for his fellow Senate colleagues, and a champion for reform.

Matthew Yglesias writes:

Someone holding a Senate seat during a critical period but with no future political ambitions would have a pretty unique opportunity to play a kind of bold leadership role if the Senator in question were someone with the knowledge and credibility to really contribute to the debate.

I like Ezra Klein’s take best:

I’d worry that Atul himself would find it a bit of a disappointing experience, as knowing stuff is not likely to matter much at this stage in the process… But it would be a bulletproof choice, and would certainly lead to a great New Yorker article.

This jibes with my sense that the timing is off, unless the health care bill is going to take a lot longer than most people think it will. But, jeez…

It’s almost like the Senate should have a handful of at-large, two-year members who are experts on particular policy issues. They’d rotate in like non-permanent members of the UN Security Council.

(This is probably why I should not be allowed to design a system of government. It’d have epicycles all over the place. Even more than the current U.S. Senate.)

The skeins of its own legend / Tim

Like many of you, I consider myself an unofficial research assistant for Robin’s forthcoming detective story. In that vein I submit Sara Corbett’s totally true, undefinably cool NYT magazine story about the production, preservation, and immanent publication of Carl Jung’s mythical The Red Book, which sounds like something right out of Penumbra’s bookshop.

I’m just going to post part of Corbett’s overture, because I like it so much:

Some people feel that nobody should read the book, and some feel that everybody should read it. The truth is, nobody really knows. Most of what has been said about the book — what it is, what it means — is the product of guesswork, because from the time it was begun in 1914 in a smallish town in Switzerland, it seems that only about two dozen people have managed to read or even have much of a look at it.

Of those who did see it, at least one person, an educated Englishwoman who was allowed to read some of the book in the 1920s, thought it held infinite wisdom — “There are people in my country who would read it from cover to cover without stopping to breathe scarcely,” she wrote — while another, a well-known literary type who glimpsed it shortly after, deemed it both fascinating and worrisome, concluding that it was the work of a psychotic.

So for the better part of the past century, despite the fact that it is thought to be the pivotal work of one of the era’s great thinkers, the book has existed mostly just as a rumor, cosseted behind the skeins of its own legend — revered and puzzled over only from a great distance.

Which is why one rainy November night in 2007, I boarded a flight in Boston and rode the clouds until I woke up in Zurich, pulling up to the airport gate at about the same hour that the main branch of the United Bank of Switzerland, located on the city’s swanky Banhofstrasse, across from Tommy Hilfiger and close to Cartier, was opening its doors for the day. A change was under way: the book, which had spent the past 23 years locked inside a safe deposit box in one of the bank’s underground vaults, was just then being wrapped in black cloth and loaded into a discreet-looking padded suitcase on wheels. It was then rolled past the guards, out into the sunlight and clear, cold air, where it was loaded into a waiting car and whisked away.

Come on. You have to read the rest now. Dan Brown’s crap-ass Freemasons have nothing on this.

When Mom & Dad are fighting / matt

I’m not sure whether our political moment really is more polarized than it has been in the past. But boy, does it feel corrosive. Mothers are crying at the prospect of the President might speak to their children. People are sniffing everywhere for hints of racism.

I’ve been wondering quite a bit recently how democratic dialogue is supposed to occur in a situation like this. We can’t talk to each other. How on earth are we supposed to handle self-governance?

Because I think in media, I’ve been craving a documentary project on this topic. I want to hear people of all political stripes address the topic of how we practice democracy when everyone assumes everyone else is acting in bad faith. Here’s how this looks in my head:

It’s a website. A wall of videos, and an assignment: Find a collaborator, someone whose political views contradict your own. You’re given a set of questions that might help foster a productive conversation. You and your collaborator interview each other about this topic – our polarization – and how we fight it. The full video of both interviews is posted. Creative Commons, natch. Anyone who’d like can edit their own version.

Living in the future / Tim

Jason Kottke on how “the iPhone is still from the future in a way that most” single-purpose electronic devices aren’t:

Once someone has an iPhone, it is going to be tough to persuade them that they also need to spend money on and carry around a dedicated GPS device, point-and-shoot camera, or tape recorder unless they have an unusual need. But the real problem for other device manufacturers is that all of these iPhone features — particularly the always-on internet connectivity; the email, HTTP, and SMS capabilities; and the GPS/location features — can work in concert with each other to actually make better versions of the devices listed above. Like a GPS that automatically takes photos of where you are and posts them to a Flickr gallery or a video camera that’ll email videos to your mom or a portable gaming machine with access to thousands of free games over your mobile’s phone network.

I think this is a pretty big deal, because it gives Apple and other makers of multifunction devices a more competitive position. It isn’t just that the iPhone has a camera, so you don’t need another camera – it’s that the iPhone’s wireless, sync, display, and other built-in features actually make it a BETTER solution for taking mobile pictures than any standalone camera.

This suggests a solid principle for multifunction devices (which also happens to be the one proffered by Umair Haque) – not innovation, but awesomeness. Adding extra features alone only adds value arithmetically, if that. (Sure, it’d be nice if the Kindle also had a calculator, but it wouldn’t really make it any better as a reader.) Extra features that in turn make each other work better adds value geometrically, at least. And the iPhone’s base of being a portable device with a nice screen, good UI, wireless connectivity, and ability to sync with a computer and cloud store — all, except wireless, foundational technologies of the original iPod — give it an incredibly wide base for adding geometric value.

It’s important, too, that the iPhone, like all media devices, doesn’t just compete for attention based on its features or costs; it’s also in competition for the geography of the human body. It’s what you put in your pocket, what you mount in your living room, what you stow away in your bag when you get on an airplane.

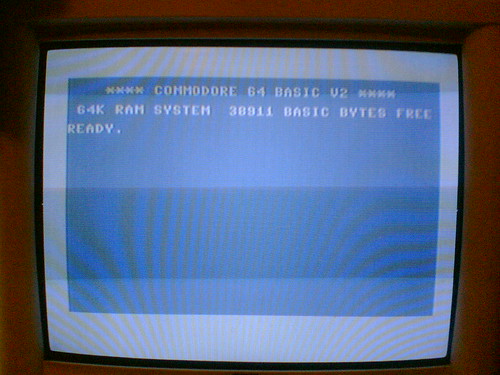

My first "video" game / matt

After we retired the Atari, my brother bequeathed me his Commodore 64 and his collection of 5.25″ floppies. Few of the disks had proper labels. Here and there you could make out a word crummily penciled onto an aging sticker. I dimly understood that most of the set had been copied from copies of software owned by my brother’s friends, but mostly, I just knew that they were mine now.

After we retired the Atari, my brother bequeathed me his Commodore 64 and his collection of 5.25″ floppies. Few of the disks had proper labels. Here and there you could make out a word crummily penciled onto an aging sticker. I dimly understood that most of the set had been copied from copies of software owned by my brother’s friends, but mostly, I just knew that they were mine now.

Far too much of my childhood was spent methodically inserting floppy after floppy and uttering the magic words that would reveal its secrets: LOAD "$",8,1

A jumble of code would cascade onto the blue screen, the processor would begin to whir, and after a few minutes, more often than not, it would groan and cough and settle to a halt. This meant the disk had been corrupted.

But every now and then, I’d slip in a disk and something marvelous would occur: inside the computer I could hear a stirring accelerating into flight, the cursor on the screen would disappear, the field of blue would change to black or white, and a program would begin.

Read more…