Slate tackles the book trailer / matt

Our own indispensable @SaheliDatta points to Slate’s takedown of the proliferating book-trailer genre. The column is skeptical of book trailers, but I tend to find them charming. I remember loving the idea when I first ran across it, and now we’ve got several exemplars of the form, like the Little Prince Pop-Up Book trailer:

I like the way book trailers attempt to light up your expectation for a printed page by teasing you with an entirely different sort of temptation. A good book trailer is like good food photography. I don’t think of the primary seduction of a meal as being visual, but a well-done food photo evokes everything non-visual about a meal – taste, scent, texture. Similarly, I don’t typically think of the primary seduction of a book as being its atmosphere or aesthetic, but this is what a good book trailer (or animated book cover) evokes – the environment the book will create around you as you read it.

Obligatory Miranda July link. Obligatory Miranda July book trailer:

The We Feel Fine Book / matt

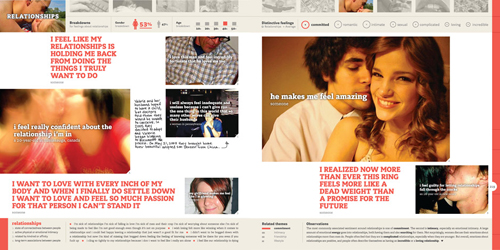

Talk about reverse publishing. One of the world’s most beautiful Web apps has been turned into a book. And it looks fantastic:

I also love that they make it easy to embed pages, even if it’s just a simple linked jpg. (How fantastic would it have been if they’d let you embed an interactive widget from the book exploration interface they created on their site, though?)

Preordered. (Via @andrewhaeg.)

The invention of content delivery, pt 2 / Tim

Kenny Goldsmith writes that

with the rise of the web, writing has met its photography

but really, writing “met its photography” 500 years ago; it was called print. Virtually everything that photography did to painting – to the entire field of visual culture – print did to writing. After print, writing was reproducible, mechanized, lost/regained its aura, chirographic/manuscript writing was displaced as a storage and reproduction technology*, etc….

(*partially at first, more completely after the emergence of the typewriter, but of course manuscript never goes away, as any trip to a doctor’s office will show you)

So it would in fact be fairer to say not that “writing met its photography” with any technology, but rather that in photography, painting met its print.

Now, I love that Goldsmith tees up Peter Bürger on this score, because I would like to do the same. This is Goldsmith quoting Bürger:

In 1974, Peter Bürger was still able to make the claim that “[B]ecause the advent of photography makes possible the precise mechanical reproduction of reality, the mimetic function of the fine arts withers. But the limits of this explanatory model become clear when one calls to mind that it cannot be transferred to literature. For in literature, there is no technical innovation that could have produced an effect comparable to that of photography in the fine arts.” Now there is.

Absolutely. But — again — two things. First, and this may be obvious, but print DID produce an effect on literature and literary production comparable to that of photography in the fine arts. The relevant books here are Marshall McLuhan’s The Gutenberg Galaxy, Elizabeth Eisenstein’s The Printing Press as an Agent of Change, Benedict Anderson’s Imagined Communities, and hundreds if not thousands of others. I hope this doesn’t need to be shown.

But neither Bürger nor Goldsmith are really interested (alas!) in the late Renaissance. They’re primarily interested in the emergence of the avant-garde in the twentieth. Photography spun off Impressionism, Cubism, Futurism, Abstract Expressonism, Pop Art — where did avant-garde writing come from? Obviously writers were reacting to photography and film, too, but it didn’t affect them (so the argument goes) in the direct way it did visual artists. So whence the avant-garde? For Bürger and Goldsmith both, there is no explanation – for Goldsmith, this means (in part) that the real avant-garde, the final clearing away of all the traditionalist residue in literature, can finally begin.

I want to offer an alternate solution by pointing to the following: the newspaper, wood-pulp paper, the fast/continuous press, the telegraph, the typewriter, carbon paper, half-tone photographic reproductions, lithography and offset printing, the mimeograph, the file cabinet.

For Bürger and Goldsmith, having traversed this history, all of these writing technologies seem totally natural. But they are not. This was an honest-to-goodness information revolution, which — we ought not to be surprised by this — coincides with both the industrial revolution and the broader media revolution that includes photography and cinema. (I’m not proposing anything radically new here either – see Friedrich Kittler’s Gramophone, Film, Typewriter, Bernhard Siegert’s Relays, Avital Ronell’s The Telephone, and especially Harold Innis’s Empire and Communications, Charles Olson’s “Projective Verse,” among many others.)

The important point is that the Dada cut-up, Pound’s and Eliot’s use of fragments/quotations, Joyce’s and Apollinaire’s riffing with typography, Mallarmé’s reimagining of the book, and Kerouac’s continuous scroll don’t come out of nowhere. Nor are they somehow just rehashings of the Gutenberg moment, no matter what Hugh Kenner says in The Stoic Comedians — not least because he argues against himself in The Mechanic Muse.

We can have a new avant-garde without pretending that the old one happened for no reason, or that it never happened at all.

(I’m not nearly done yet! Part 3 is coming! I’ll actually talk about “content distribution”! Dematerialization! Video games! Waaahhh!)

The invention of content delivery, pt 1 / Tim

A while back, the conceptual writer Kenny Goldsmith wrote something really high-concept:

with the rise of the web, writing has met its photography

I actually can’t find the original 2007 blog post where Kenny wrote this – the link above takes you to . But luckily, he reformulated it in July in a comment on Ron Silliman’s blog:

As I’ve said before on the Poetry Foundation, with the rise of the web, writing has met its photography. By that I mean, writing has encountered a situation similar to what happened to painting upon the invention of photography, a technology so much better at doing what the art form had been trying to do, that in order to survive, the field had to alter its course radically. If photography was striving for sharp focus, painting was forced to go soft, hence Impressionism. Faced with an unprecedented amount of digital available text, writing needs to redefine itself in order to adapt to the new environment of textual abundance.

When we look at our text-based world today, we see the perfect environment in which writing can thrive. Similarly, if we look at what happened when painting met photography, we’ll find that it was the perfect analog to analog correspondence, for nowhere lurking beneath the surface of either painting, photography or film was a speck of language. Instead, it was indexical — image to image — thus setting the stage for an imagistic revolution. Today, digital media has set the stage for a literary revolution. In 1974, Peter Bürger was still able to make the claim that “[B]ecause the advent of photography makes possible the precise mechanical reproduction of reality, the mimetic function of the fine arts withers. But the limits of this explanatory model become clear when one calls to mind that it cannot be transferred to literature. For in literature, there is no technical innovation that could have produced an effect comparable to that of photography in the fine arts.” Now there is.

Ninety percent of me is so sympathetic to everything that Goldsmith says here. And it sounds familiar, right? Digital tech has revolutionized reading, spun off all sorts of new writing process, and poses the potential to continue to revolutionize writing. I agree with all of this.

It’s that ten percent of me — that part that thinks about the nineteenth century more than I really ought to, which is also the part that takes analogies way too seriously — that can’t let it go. Not for the claims, but for the analogy used to make them —

web: writing :: photography: painting

— which I love for its rhetoric, its purity, its lightning flash, but can’t accept as an historical analysis.

I think the analogy can be fixed by changing one word. Instead of “writing,” say “publishing.” Even though I know Kenny means “writing,” that he, like me, is really concerned first and foremost with writing and less with other kinds of media, I want to say that he really means “with the rise of the web, publishing has met its photography.” Let me explain why.

First, painting is fundamentally different from photography in ways that writing is not different from the web. As Kenny points out, the web IS writing – an unprecedented amount of text. The web is not only writing, but writing belongs to the web in a way that painting does not and could not belong to photography. For Goldsmith to keep “writing” and “the web” distinct, he’d have to define “writing” in traditionalist literary terms he wouldn’t want to accept, or “the web” in terms that likewise make it quite foreign to text, and he can’t do that either.

It’s important to remember that photography didn’t only pose a crisis for painting, but for all of visual art. That’s where Goldsmith’s conceptual predecessor Marcel Duchamp comes in with his ready-mades. Photography also transformed theater, journalism, bookmaking, advertising… There’s no reason to single out painting.

Likewise, writing isn’t the only kind of cultural production that’s been upended by the web. Television, movies, still photographs, telecommunication — everything that fits under the increasingly wide banner of “content delivery” is affected by the web according to much of the same logic that the web has been affecting writing.

In short, “the web” is not a medium – at least not in the same sense that photography is. It is a content delivery system, that not only represents and reproduces content but also stores and delivers it. For most people, this change in content delivery has offered remarkable change, but has not posed a crisis of the same sort felt by painters and sculptors and playwrights in the wake of photography. It’s not writers who face a crisis, but publishers.

So, then:

web:publishing* :: photography:visual culture**

*in the 20th/21st century

**in the 19th/20th century

Maybe that isn’t quite the lightning bolt as Goldsmith’s original formulation, but I think it’s closer to the truth.

The Useless Iconoclast / matt

A couple of months ago, I started typing up a long post bashing David Goldhill’s Atlantic Monthly cover story on health care that everybody was lauding (especially David Brooks). The article had appeared in the midst of August, when health care reform was on the ropes, and it seemed like just another antagonist helping to push the process to defeat. But by September, when I was drafting the post, the prospects for reform had brightened dramatically. It was revived! With a public option! In the Senate, even! So I put my post away.

Another article, in the New Yorker this time, is getting my dander up again. (OK, it’s a blog post, but for any other publication it would have been an article.)

These articles perpetuate the belief rampant in journalism that systemic change happens in sweeping gestures. And very, very occasionally, it does. But over the past 90 years, almost every sweeping change proposed to overhaul the health care system has gone down to crushing defeat. The real changes have been step by step, bit by bit. Even Medicare when enacted was a mere condolence for the death of the comprehensive insurance system Truman had envisioned 20 years before.

But the worst thing about these articles is that they’re not content to just paint a grander vision than is practical or possible. They also spit at the seeds of change reformers have fought hard to embed within the legislation that’s proceeding.

At the heart of both Cassidy and Goldhill’s arguments is a familiar contention and one I agree with – that one of the biggest problems with the US health care system is the way it distorts costs by shuffling most payments for health care through a gruesome patchwork of employers and private insurers. Goldhill would reboot the current system in favor of a more libertarian solution, establishing affordable options for catastrophic coverage and handing out vouchers for individuals to purchase more routine care. Cassidy suggests he’d like a more progressive solution, perhaps straight-up single-payer insurance.

If their arguments stopped there, I’d appreciate them. Either of these proposals could be part of a good conversation about what health reform might look like in an ideal world. And I think it’s tremendously important that folks continue to paint these alternative visions of what health care can become.

What I find most maddening about these articles, though, is the pose of the lonely iconoclast. The way the authors pretend their ideas are so novel and transgressive that no one’s pointed them out until now. The way they ignore the past 90 years of attempts at health care reform. And worst, worst of all – the way they off-handedly dismiss the real reforms that try to incorporate those ideas into actual legislation as pragmatically as politics allows.

Both men frame their arguments as though they’re the hard-headed realists pointing out the truths no one else will acknowledge. But both are ignoring (or dismissing) reality themselves, not even really engaging with politics as it exists in the real world.

If you don’t mind a bit of wonkiness, read on. Read more…

The real sea change / Tim

Bob Stein at if:book, “Sea Change“:

There was a book sale outside the library at UCLA today. lots of wonderful paperbacks for 50 cents each. a year ago i would have bought a bag full. today zero. why? i do almost all my novel reading now on my iPhone which is always with me and which makes it easy to read at the gym, as opposed to print books which never lie flat.

This is funny. If I’d seen the same curbside sale of cheap paperbacks, I’d want to read them on my iPhone, too.

But I’d still buy a bag full, maybe two. Then I’d joint the books — cut the cover off and pull the pages apart, one by one — and run them through a two-sided scanner, OCR them, and save them as PDFs, HTML, etc., so I can make MOBI and EPUB and every other e-book format of them. Then I’d read them on my iPhone, my computer…

This is a two-step dance, folks.

The kids are alright / Tim

I love this man — more than I loved Carl Sagan or Richard Feynman or Mr Wizard or the detectives on MathNet.

| The Colbert Report | Mon – Thurs 11:30pm / 10:30c | |||

| Neil deGrasse Tyson | ||||

|

||||

I’m glad my children get to have him.

Love in the time of Twitter / Tim

David Brooks thinks cellphones are bad, bad, bad! not just for our brains, but for romantic love:

Once upon a time — in what we might think of as the “Happy Days” era — courtship was governed by a set of guardrails. Potential partners generally met within the context of larger social institutions: neighborhoods, schools, workplaces and families. There were certain accepted social scripts. The purpose of these scripts — dating, going steady, delaying sex — was to guide young people on the path from short-term desire to long-term commitment.

Over the past few decades, these social scripts became obsolete. They didn’t fit the post-feminist era. So the search was on for more enlightened courtship rules. You would expect a dynamic society to come up with appropriate scripts. But technology has made this extremely difficult. Etiquette is all about obstacles and restraint. But technology, especially cellphone and texting technology, dissolves obstacles. Suitors now contact each other in an instantaneous, frictionless sphere separated from larger social institutions and commitments.

People are thus thrown back on themselves. They are free agents in a competitive arena marked by ambiguous relationships. Social life comes to resemble economics, with people enmeshed in blizzards of supply and demand signals amidst a universe of potential partners.

You know, I actually really like David Brooks. I think Bobos In Paradise was a terrific book; I stick up for his place on the NYT Op-Ed masthead; his stuff on neuroscience has been really good; and I’m delighted whenever I see him on TV, on Jim Lehrer or Chris Matthews, because he seems to think and talk like a regular guy. Okay, a regular guy who went to the University of Chicago and never really left. But I never really left either, so I get that too.

But there’s a reason why he called it the “Happy Days” era: the past he’s describing isn’t really the past, but a 70s-era TV version of the past. Not even the past’s representation of itself! For that, you’d have to see On the Waterfront or read On the Road or Giovanni’s Room. It’s memory as ideology, created (whether consciously or unconsciously) to surreptitiously win arguments about the present, especially about social morés and generational change.

And the Happy Days era — the real one, which was reflected in the TV show like a funhouse mirror — was driven by technological and social change, too! Kids had access to cars, telephones, TV, records and the radio, and disposable cash. Cruising, malt shops, high school dances, drive-in movies, everything you see in American Graffiti — it might feel like part of the timeless social ritual now, but then, it was a revolution, a set of truly radical acts. Add the pill, civil rights, and a swelling in the ranks of college students, and you’ve got feminism, counter-culture, the sexual revolution. But in some ways, this was a postscript. The most important changes, the subterranean ones, had all happened already.

That’s me taking up Brooks for his treatment of the past. Ezra Klein – who has a much firmer grounding in the realities of the present than Brooks- also takes aim:

Columns like Brooks’s irk me because they demean not only my lived experiences, but those of everyone I know. To offer a slightly more modern rebuttal, Sunday was my one-year anniversary with my girlfriend. A bit more than a year ago, we first met, the sort of short encounter that could easily have slipped by without follow-up. A year and a week ago, she sent me a friend request on Facebook, which makes it easy to reach out after chance meetings. A year and five days ago, we were sending tentative jokes back-and-forth. A year and four days ago, I was steeling myself to step things up to instant messages. A year and three days ago, we were both watching the “Iron Chef” offal episode, and IMing offal puns back-and-forth, which led to our first date. A year ago today, I was anxiously waiting to leave the office for our second date.

It is not for David Brooks to tell me those IMs lack poetry, or romance. I treasure them. Electronic mediums may look limited to him, but that is only because he has never seen his life change within them. Texting, he says, is naturally corrosive to imagination. But the failure of imagination here is on Brooks’s part.

Paper anniversary / Tim

Today is my one-year anniversary of writing for Snarkmarket.

I should say — my anniversary of writing as an author, because I was the unofficial commenter-in-chief long before that. Snarkmarket was the first blog I read; it inspired me to start my own, which (being even nerdier than Matt and Robin) I bestowed with the German pun Short Schrift; and I think it also helped me to realize that the problems I’d been thinking about in philosophy and literature and politics and elsewhere revolved around problems in media — and for me, specifically, media that had something to do with writing.

It’s been really cool, to use the parlance of our times. When I describe Snarkmarket to people who’ve never read it (especially if they’ve never read a blog), I say that the three of us – a journalist, an academic, and a media producer (does anyone know exactly what to call Robin?) write about how these three fields and everything they touch (which is everything) change — with all of us writing about everything, under the assumption that one important change is the redefinition of intellectual/professional boundaries.

Now, I like the indefinite tense on “change,” because Snarkmarket has always been tense-agnostic; we all write about the past, present, and future. If I skew towards the past, Robin towards the future, and Matt towards the present — I’m not completely sure that we do, but that’s what you might predict — it all somehow becomes quite coherent.

I think the root of that coherence may be that Matt, Robin, and I are all in love with writing, in all of its forms.

I deliberately give “writing” a very broad meaning, both materially and conceptually — which is nevertheless a very literal meaning. It’s not an accident that in my entry for “photography” in the New Liberal arts, I define it even more literally as “the writing/recording of light.” It bothers me when otherwise intelligent people implicitly limit writing to either handwriting or print, the writing that fills up books or fills out our signature. It’s not true. Writing — and reading — are everywhere, in almost every medium. It’s not even worth listing them all. We’re saturated in literacy.

The assumption that usually goes along with this reductive view of writing — setting aside ritual genuflections before the ghost of Gutenberg and his machine — is that reading and writing are essentially ahistorical, almost natural, assumed parts of the educated order, at least for moderns like us, while other technologies are unnatural interruptions of this order. Or, that once key technologies are discovered/invented – e.g., script, the alphabet, the codex, or print – their history stops, and they proceed along, virtually unchanged, until the present.

I once heard Marilyn Frye, a philosophy professor at Michigan State, describe this as the point-to-point view of history. In 1865, Lincoln abolished slavery; in 1920, the 19th Amendment guaranteed women the franchise — and after each event, nothing else happened, at least to women or black people in the United States. Ditto, Johannes Gutenberg invented movable type in 1439, after which, nothing else happened, writing no longer has a history.

For instance — and I don’t want to unfairly pick on something tossed off during an interview, but here we are — Brian Joseph Davis, interviewing Michael Turner for The Globe and Mail, flatly asserts that the book “is stalled out, in terms of technology, at 1500 AD, and sociologically at around 1930.” See Jason Kottke’s post, “Books have stalled,” where he quite rightly asks what these dates might mean.

On the technology side, Davis is just flatly wrong. I’d invite him to operate an incunabula letterpress — set the type, prepare the pages, swab the ink, and crank the mechanical lever page by page — and then visit a contemporary industrial press before he felt tempted to say something so silly again. (If he’s only talking about the codex form of the book, and not the means of production, then he actually needs to run back over a millennium — and even then, the size and shape and composition of books has steadily changed over those 500+ years too.)

We also don’t print on parchment anymore. Gutenberg did print a bunch of bibles in paper, but it was cloth paper — the fancy stuff we print our resumés on now — not the kind of paper we use today. Davis should read a few 19th-century histories and manuals of papermaking — they’re free on Google Books — just to realize what a technological triumph it was to create usable paper out of wood-pulp. You can’t just smash up some trees — it’s a chemical process that’s as complicated as creating and developing photographic film, a breakthrough that happened around the same time (the two are actually related.) Turning that into an industrial production that could make enough paper to print books and newspapers and everything else in the nineteenth century was another breakthrough.

This is what the industrial revolution did for us, folks. It wasn’t all child labor and car parts. It changed the way we made and consumed culture.

For the last 500 years, ours has been a culture of paper. But the East had paper for centuries before, and what we call paper completely changed a little more than a century ago. It’s convenient if you want to either attack or defend book culture to paint it as unchanged by the passage of time, but it just isn’t so.

Add in all of the cataloguing and distribution technology developed in the twentieth century, shifts in marketing, the rise of chain retail and online booksellers – the kind of stuff that Ted Striphas writes about in The Late Age of Print — and it’s clear that there wasn’t just one revolution (Gutenberg’s) that made the past and another (digital media) that’s making the present and future. We are dealing with a long, intersecting history of multiple media, each of which are heterogeneous, that is ongoing.

Anyways, that is the past, and the present. I hope you will stay with us for the future. So far, I’ve loved this show. I can’t wait to see what next.

Unintentional Simultaneous Coda (from Matthew Battles, writing about something quite different):

Of course there is intention and purpose in the system, Smail allows, but it’s personal, limited in space and time, not a case of grand, scheming ideological structure.

What’s in this for me? Well, it’s a handy and inspiring way to think about the rise of writing in general, and of specific letterforms, as memes facing selection pressures that change with dips and explosions in media, genres, and social and cultural forms. So there’s a retrospective use, helping to understand the existence of stuff like serifs and dotted i’s thrive while eths and thorns and a host of scribal abbreviations die out. And prospectively, it help enrich my sense of the future of reading and writing—mostly by reminding me that it will be decided by no business plan or venture capitalist, but by all of us getting in there, using and breaking the new tools, and making new things and experiences with them.

Absolutely. Now all we have to do is get there.

BYO Birthday remix / matt

In honor of Tim Carmody and Snarkmarket, which have their 30th and 6th birthdays today, respectively, here’s a DIY music/movie mashup courtesy of two others also born on November 3rd.

First, press play on this aria by Vincenzo Bellini (b. 11/3/1801), from his opera Norma:

While you’re enjoying that, pull the volume on this second clip down to mute. (The video comes from Snow White, whose chief illustrator was Gustaf Tenggren, b. 11/3/1896.) When Norma hits the 1:18 mark, press play:

Happy birthday to Tim, Snarkmarket, and all the other producers of beautiful things born on November 3.