The invisible down / Tim

This Sports Illustrated article on NFL punters is well-worth reading. Two things that the article alludes to but doesn’t make a big deal about:

- Punters, in addition to booting the ball away and trying to pin down the other team’s defense on fourth down, also often hold for the placekicker on extra points and field goals. Not only can a dropped or bad hold lose games (more high-pressure stakes for already high-pressure players) but an athletic punter gives you a lot more options for fake kicks. (Another reason why a lot of punters were high-school or college quarterbacks.)

- For NFL players, punters have amazing longevity. I was amazed that Ray Guy, a legendary punter I remember watching in the mid-80s, when I first started watching football as a kid, is now 60 years old, and that Giants punter Jeff Feagles is still one of the best in the league at 43.

This last point, though, made me think about this point Malcolm Gladwell made in his exchange with Bill Simmons, about concussions, other head impacts, and the reduction in life expectancy for most other NFL players:

Early in the 20th century, there was a big movement to ban college football because of a rash of deaths on the field, and one of the innovations that saved the game was the legalization of the forward pass. What people realized was the more you open the game up, and make the principal point of physical contact the one-on-one tackle in the open field, the safer the game becomes. Keep in mind, the forward pass at the time was a radical step. Lots of diehard types stood up at the time to say that passing would ruin football. But it happened anyway. So there’s a precedent for dramatic reforms in football, even those that change the spirit of the game. I think football has to have that same kind of radical conversation again. What if we made all tackles eligible receivers? What if we allowed all offensive players to move prior to the snap? What if we banned punt and kickoff returns, where a disproportionate number of head impacts happen? [emphasis mine]

In SI, Feagles talks about how punting has changed over his career:

Just 10 years ago there were probably only a handful of returners who could take a punt and run it back; the athletes covering the kicks were much better than the returners. But the tide has turned. Nowadays the returners are much better than the guys covering. What does that do to the punter? It puts more pressure on him to directional kick and to keep the ball out of the returners’ hands.

So the “golden age of punting” coincides with the golden age of concussions; punters and returners have both gotten better, which puts more pressure on coverage guys on both sides of the ball; and those are the guys getting dinged, injuries that contribute to disproportionately shorter lives and careers for non-punters — for a part of the game that even fans and sportswriters don’t fully appreciate. (As the SI article explains, no pure punter has ever been voted into the Hall of Fame).

I hate to say it, but maybe that Canadian is right.

The looming public/private divorce / matt

I woke up this morning intending to get an early start. As always, I pulled out my phone before I’d even put on my glasses, and thumb-flipped through my RSS reader a bit. Then, just as my attention span was about to hit its limit, someone casually dropped a link to James Fallows’ cover story in the new Atlantic, titled “How America Can Rise Again.” Hook, line, sinker.

This might be the first Fallows story I’ve read that over-promises and under-delivers. Reading it doesn’t really give you anything in the way of insight about how America can rise again. This is about as close as Fallows gets to future-pointed pep talkery:

Our government is old and broken and dysfunctional, and may even be beyond repair. But Starr is right. Our only sane choice is to muddle through. As human beings, we ultimately become old and broken and dysfunctional—but in the meantime it makes a difference if we try. Our American republic may prove to be doomed, but it will make a difference if we improvise and strive to make the best of the path through our time—and our children’s, and their grandchildren’s—rather than succumb.

It doesn’t get much cheerier than that. The piece feels as though Fallows is trying – and failing – to convince himself he’s worrying too much about America’s decline. He brings up several reasons to discount pessimism about the country’s future, and then winds up delivering the most pessimistic argument of all. “Most of the things that worry Americans aren’t really that serious, especially those that involve ‘falling behind’ anyone else,” he says, by way of setup, and then continues: “But there is a deeper problem almost too alarming to worry about, since it is so hard to see a solution. Let’s start with the good news.”

When I finished it, my feelings were somewhat akin to those I felt after I read his September 2009 cover story declaring victory in Iraq. I’d been lured in by a bombastic cover treatment proclaiming, “We won!” At the end, the most resonant message to emerge from the piece was, “Let’s cut our losses.”

There’s a wealth of ideas threaded through Fallows’ latest – the worthy tradition of the American jeremiad, the “innocence” of Mancur Olson, the power of young, unproven scholars in American academia. I thought the most provocative invocation in the piece was his assertion that the situation in California is giving us a first taste of an impending public-private divorce. But there’s not really a big idea or a thesis statement. I didn’t really know what to do with it, so I brought it here.

PS: Sorry I’ve been so quiet lately. I’m somehow supposed to be moving to DC in three weeks. A post about that is forthcoming.

I dunno… seems a little "wiki" / Tim

This story about NYC’s Murray’s Cheese Shop‘s Cheese 101 program is pretty good, but I took note of one phrase in particular:

We sampled six cheeses, drank wine and champagne, and learned that cheese was invented in Mesopotamia around 3000 B.C., when travelers carrying milk around in the sun in dried-out sheep stomachs noticed that it had begun to curdle and become delicious (this story sounded suspiciously Wiki to me, and indeed here it is, given as one possible explanation).

“This story sounded suspiciously wiki.” The obvious colloquial analogue would be “the story seemed fishy.” But note the distinction. A “fishy” story, like a “fish story,” is a farfetched story that is probably a lie or exaggeration that in some way redounds to the teller’s benefit. A “wiki” story, on the other hand, is a story, perhaps farfetched, that is probably backed up by no authority other than a Wikipedia article, or perhaps just a random web site. The only advantage it yields to the user is that one appears knowledgeable while having done only the absolute minimum amount of research.

While a fishy story is pseudo-reportage, a wiki story is usually either pseudo-scientific or pseudo-historical. Otherwise, wiki-ness is characterized by unverifiable details, back-of-the-envelope calculations, and/or conclusions that seem wildly incomensurate with the so-called facts presented.

This story about an extinct race of genius-level hominids turns out to be decidedly wiki.

Have folks heard this phrase in the wild? Is it unfair to Wikipedia, or to those who use it as a research source? Do we already have a better word to describe this phenomenon? (And: this phenomenon is all too real, and deserves a name, doesn’t it?)

Collateral damage / Tim

I just posted this as part of a comment at Bookfuturism, and am curious to know what the Snarkmatrix makes of it. Partly because I’m not entirely sure myself!

(Short context: it was responding to a post and commenter who took issue with the idea that reading, especially literary reading, was just “a method of digesting information.”)

You could say that certain kinds of information work better in some media than others, likewise certain kinds of entertainment, or for intellectual reasons, like working through a philosophical or literary text, or for that matter a self-help book. (These might not be your thing, but I’d contend that the mix of aesthetic and psychological intent is about the same.)

But it starts to become hard to say things like “information belongs to the web, literature to print,” because it’s all about what kind of information, what kind of literature. Every genre finds different ways to work a medium to its advantage.

Maybe this is a different way of addressing the question; is it inevitable that certain media become dominant, even if they’re not as well-suited for the purpose at hand? For instance, you could say that it’s better in the abstract to read a magazine or shop with a clothing catalog in print, rather than on the web. (For the sake of argument, let’s grant this.) But once the web becomes the source of most of our information, in the form of news, search results, or references, and the most effective way for advertisers to target and reach their customers, print loses anyway; its inherent advantages don’t matter, because both readers’ behavior and sellers’ incentives have moved somewhere else.

This is essentially what defenders of newspapers have argued; journalism is best suited to the specific culture and medium of print newspapers (rather than TV or blogs), and so we need to find some way to offset that it’s no longer best-suited for full-page or classified ads. If the newspaper goes, investigative journalism goes with it. That, at least, is the argument.

Ditto booksellers. It doesn’t matter if you don’t want to buy a Moleskin notebook, wrapping paper, or a copy of the Sarah Palin autobiography; maybe it belongs at Wal-Mart or Best Buy. The fact is, if your bookstore can’t sell at least a fistful of those hardcovers at cover price, they stop being able to function as a going concern — so all of those things that your bookstore IS really well-suited for (seller of literary fiction, community center, whatever) get lost for reasons that have nothing to do with them.

So, is publishing like this? If Dan Brown and Malcolm Gladwell publish only in ebook, does the next Joyce or Hamsun get the chance to publish widely in print? If Joyce can publish a little run of Ulysses on Lulu in 19/2022, does it get published in a fat edition by Random House ten years later? (I don’t think Joyce ever gets published by Random House unless his book was banned for over a decade.)

I’d like to think that we live in a world where we can have everything and give up nothing, where every act of reading can at least in principle find the medium, presentation, and audience most appropriate to it — but that assumption still remains to be shown.

Unicorn hunter roundup / Tim

Yesterday, I wrote:

Apple might be the only technology company that inspires its own fan fiction.

This was in response to this article in Macworld, “Four reasons Apple will launch a tablet in 2010,” where tech analyst Brian Marshall got to speculate that Apple was REALLY launching a tablet so that it could LATER launch a new Apple TV that included a built-in high-def screen and cost $5000. A “real” Apple TV.

I mean, sure, why not?

A lot of the “journalism” about the new tablet has been total fantasy league stuff. I’ve been there. It’s fitting that the mythical Apple tablet device has been nicknamed “the unicorn”: in Naming and Necessity, the philosopher Saul Kripke points out that while we all think we know what we mean when we say “unicorn,” in different possible worlds a unicorn could have wildly varying physiologies. A unicorn could have gills. It could photosynthesize. It doesn’t make sense to say “unicorns are possible,” because nobody could know from that statement alone what that might mean. Ditto the Apple tablet.

But Nick Bilton appears to have some actual sources on this, so the thing might very well be real. You might very well be riding a unicorn by the end of this year. I believe in the rumors enough that I cancelled my Nook pre-order to wait this thing out and see what happens. (How many customers has B&N lost by not getting that thing shipped out by Christmas? Eh — maybe the initial software would have been even more sluggish.)

In anticipation of whatever the heck might happen at the end of January, here I’ve rounded up the best four posts I’ve seen about the maybe/maybe not tablet.

John Gruber at Daring Fireball, “The Tablet“:

Do I think The Tablet is an e-reader? A video player? A web browser? A document viewer? It’s not a matter of or but rather and. I say it is all of these things. It’s a computer.

And so in answer to my central question, regarding why buy The Tablet if you already have an iPhone and a MacBook, my best guess is that ultimately, The Tablet is something you’ll buy instead of a MacBook.

I say they’re swinging big — redefining the experience of personal computing.

It will not be pitched as such by Apple. It will be defined by three or four of its built-in primary apps. But long-term, big-picture? It will be to the MacBook what the Macintosh was to the Apple II.

This is a cool idea, especially insofar as most people don’t really need to do everything current laptops and desktops do. This gets elaborated by Marco Arment, who doesn’t really talk about the tablet as much as map our current ecology, in “‘The Tablet’ and gadget portability theory“:

Desktops can use fast, cheap, power-hungry, high-capacity hardware and present your applications on giant screens. They can have lots of ports, accept lots of peripherals, and perform any possible computing role. Their interface is a keyboard and mouse, a desk, and a chair. They’re always internet-connected, they’re always plugged in, they always have their printers and scanners and other peripherals connected, and their in-use ergonomics can be excellent. But you can only use desktops when you’re at those desks.

iPhones use slow, low-capacity, ultra-low-power hardware on a tiny screen with almost no ports and very few compatible peripherals. They can do only a small (albeit useful) subset of general computing roles. They are poorly suited to text input of significant length, such as writing documents or composing nontrivial emails, or tasks requiring a mix of frequent, precise navigation and typing, such as editing a spreadsheet or writing code. But they’re always in your pocket, ready to be whipped out at any time for quick use, even if you’re standing, walking, riding in a vehicle, eating, or waiting on a line at the bank. You can carry one with you in nearly any circumstances without noticing its size or weight.

Laptops are a strange, inefficient tradeoff between an iPhone’s portability and a desktop’s capabilities. They don’t satisfy either need extremely well, but they’re much closer to desktops than they are to iPhones. The usefulness and portability gap between a laptop and an iPhone is staggeringly vast (1:00). You don’t have them with you most of the time, they’re big and heavy (even the MacBook Air weighs 10 times as much and consumes about 10 times as much space as an iPhone 3GS), and they can only be practically used while sitting down (or standing at a tall ledge). Ergonomics are awful unless you effectively turn them into desktops with stands and external peripherals. But they can do nearly any computing task that desktops can do, and they’re able to replace desktops for many people.

This is something I’ve noticed about my own computer habits. I have a mid-2008 MacBook Pro. I love its portability, but largely just because I can detach from my desk and move it around the house. I really hate lugging my laptop across town to work, on planes for trips, or anywhere that I can’t immediately get myself settled — all the more so since I lost most of the strength in my arm.

My MBP isn’t really a portable computer, but a desktop on casters, if you get my meaning. I’ve thought about getting a MacBook Air, but it’s too expensive, or a cloudbook, but those are too cheap. So I’m actually already in this market.

Whatever the Unicorn is, it will be a genuinely portable computer, like the iPhone. And it won’t make precisely the same tradeoffs in power and functionality as either the iPhone or the MacBook Air in order to do it.

I think my favorite post is by Ars Technica’s John Siracusa, who brings Ockham’s Razor to bear on the rumors and speculation with surprisingly satisfying results:

There’s also the popular notion that Apple has to do something entirely new or totally amazing in order for the tablet to succeed. After all, tablets have been tried before, with dismal results. It seems absurd to some people that Apple can succeed simply by using existing technologies and software techniques in the right combination. And yet that’s exactly what Apple has done with all of its most recent hit products—and what I predict Apple will do with the tablet.

That means no haptic-feedback touchscreen, no folding/dual screens, no VR goggles or mind control. Instead of being all that people can imagine, it’ll just be what people expect: a mostly unadorned color touch screen that’s bigger than an iPhone but smaller than a MacBook. If I’m being generous, I’ll allow that maybe it’ll be something a bit more exotic than a plain LCD display. But there are hard and fast constraints: it must be a touch screen, it must be color, and it must support video. (We’ll see why in a bit.)

So how will an Apple tablet distinguish itself without any headline technological marvels? It’ll do so by leveraging all of Apple’s strategic strengths. Now you’re expecting me to say something about tight hardware/software integration, user experience, or “design,” but I’m talking about even more obvious factors.

* Customers – Apple has over 100 million credit-card-bearing customer accounts thanks to the success of iTunes.

* Developers – Over 125,000 developers have put over 100,000 iPhone OS applications up for sale on the App Store. Then there are the Mac OS X developers (though of course there’s some overlap). Apple’s got developers ready and able to come at the tablet from both directions.

* Relationships – Apple has lucrative and successful relationships with the most important content owners in the music and movie businesses.These are Apple’s most important assets when it comes to the tablet, and you can bet your bottom dollar that Apple will lean heavily on them. This, combined with Apple’s traditional strength in design and user experience, is what will distinguish Apple’s tablet in the market. It will provide an easy way for people to find, purchase, and consume all kinds of media and applications right from the device. It’s that simple.

Kassia Kroszer at Booksquare is even more deflationary, again in a good way, pointing out we can’t just look to a Jesus Device to solve all of our problems:

Apple is an aggressive company. Apple is a tech company. And publishing people don’t necessarily get Apple. Last week’s breathless rumor about a 70/30 split (70% to publishers) was the tip-off. 70/30 is the standard Apple split! What is missed in the fine print (what is it about fine print that makes us always overlook it?) is that this split is on sales price, cash receipts, whatever you want to call it. Apple will not (unless I seriously misjudge their business acumen) be less aggressive on pricing than Amazon and likely won’t subsidize prices. I suspect Apple will not get into bed with book publishers unless book publishers play along.

If anything, the Unicorn will be part of an interesting and diverse digital reading mix. Of course, we already have one of those — you’re using it right now — and very few publishers are exploiting the potential of what already exists. The Unicorn won’t be running an exotic new platform with magical capabilities.

So let’s recap. It’ll be more portable and more fun than the best laptop you’ve ever had. You’ll be able to enjoy more content than you’ve ever been able to on your iPod, iPhone, or Apple TV. It’ll be faster, more versatile, and more beautiful than any dedicated reading machine. And while it won’t “save” publishing, it will probably be one of the major catalysts that prod it towards the future.

And this is only if what everyone admits to be true is true.

I think that’s worth waiting three weeks for.

I love paper so much I should marry it / Tim

We’ve featured examples of papercraft here before, but Webdesigner Depot just posted “100 Extraordinary Examples of Paper Art” that blew my mind. Here are a few choice examples, with commentary.

First are two by Peter Callesen, who gets the most exposure on the WD page. Not all of his pieces make use of negative space in this way, but I liked these the best:

The second is more hopeful:

This is by Simon Schubert, who somehow generates an MC Escher effect even though there are no actual visual paradoxes in his images. The brain just goes there anyways.

Bryan Dettmer calls these “Book Autopsies.” The grandfather of these kind of dada-cut-up-meets-book-art is Tom Phillips’s A Humument, but Dettmer’s got his own sculptural, Joseph Cornell-ish style:

I wonder what tools Bovey Lee uses to make these — an exacto-knife? A scalpel? A laser? The word I keep returning to is filigree:

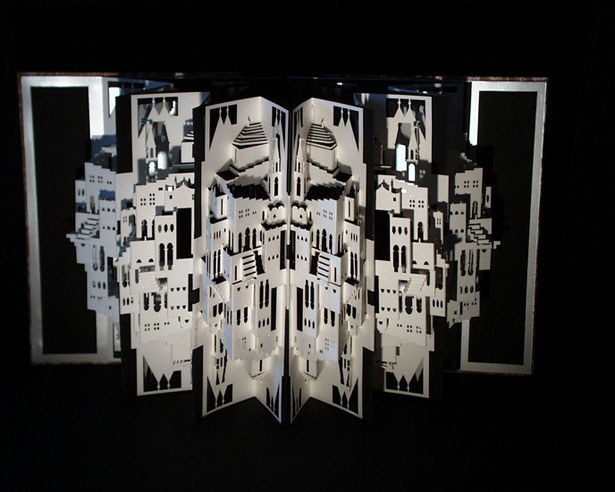

Ingrid Siliakus threads the needle here — her sculptures suggest futurism, but also cartoons and pop-up books. I like her pieces above all for their exploration of depth — you need just the right kind of photographic angle and lighting to gain a sense of their dimensionality:

Which offers some lessons on both papercraft and (perhaps) the future of paper. First: paper art isn’t just the crafting of these objects; it’s their staging, framing, lighting, and above all their photography. Black-and-white art, in particular (which I gravitate towards) is particularly sensitive to the effects of light, shadow, and differences from one angle to the next.

Last, virtually all of these pieces take advantage of the fact that a sheet of paper is a three-dimensional object posing as a two-dimensional one. It flits and flutters between these two possibilities of shape and surface, flatness and thickness, which is precisely what gives it all of its charm and utility. In a world that (setting aside the UI fantasies of Iron Man, Bones, and Avatar and the experiments of Microsoft) is going to be stuck with two-dimensional digital interfaces for a long time, this most underutilized aspect of paper takes on a new significance.

I hope kids, especially, take notice of these possibilities. A rebellious message is an airplane; a love note is a rhyming game…

In Robin's wheelhouse / Tim

Just to show that my co-blogger isn’t the only one around here who can post YouTube videos of fey poppy bands with lady singer/drummers with Prince Valiant haircuts, here’s the UK’s Internet Forever with two songs I have just now heard courtesy of Tim Sendra:

Brains old and young / Tim

Today’s a day for thinking about brains, plasticity, and renewal. At least in the pages of the New York Times.

First up is Barbara Strouch, who writes on new neuroscientific research into middle-aged brains:

Over the past several years, scientists have looked deeper into how brains age and confirmed that they continue to develop through and beyond middle age.

Many longheld views, including the one that 40 percent of brain cells are lost, have been overturned. What is stuffed into your head may not have vanished but has simply been squirreled away in the folds of your neurons.

One explanation for how this occurs comes from Deborah M. Burke, a professor of psychology at Pomona College in California. Dr. Burke has done research on “tots,” those tip-of-the-tongue times when you know something but can’t quite call it to mind. Dr. Burke’s research shows that such incidents increase in part because neural connections, which receive, process and transmit information, can weaken with disuse or age.

But she also finds that if you are primed with sounds that are close to those you’re trying to remember — say someone talks about cherry pits as you try to recall Brad Pitt’s name — suddenly the lost name will pop into mind. The similarity in sounds can jump-start a limp brain connection. (It also sometimes works to silently run through the alphabet until landing on the first letter of the wayward word.)

That’s a wonderful technique, all the more so because it sounds like something Cicero might have invented.

But hey! Speaking of the alphabet, here’s Alison Gopnik’s review of Stanislas Dehaene’s Reading in the Brain. (See here for more on Dehaene, and here for my Bookfuturist response.) From the review:

We are born with a highly structured brain. But those brains are also transformed by our experiences, especially our early experiences. More than any other animal, we humans constantly reshape our environment. We also have an exceptionally long childhood and especially plastic young brains. Each new generation of children grows up in the new environment its parents have created, and each generation of brains becomes wired in a different way. The human mind can change radically in just a few generations.

These changes are especially vivid for 21st-century readers. At this very moment, if you are under 30, you are much more likely to be moving your eyes across a screen than a page. And you may be simultaneously clicking a hyperlink to the last “Colbert Report,” I.M.-ing with friends and Skyping with your sweetheart.

We are seeing a new generation of plastic baby brains reshaped by the new digital environment. Boomer hippies listened to Pink Floyd as they struggled to create interactive computer graphics. Their Generation Y children grew up with those graphics as second nature, as much a part of their early experience as language or print. There is every reason to think that their brains will be as strikingly different as the reading brain is from the illiterate one.

Should this inspire grief, or hope? Socrates feared that reading would undermine interactive dialogue. And, of course, he was right, reading is different from talking. The ancient media of speech and song and theater were radically reshaped by writing, though they were never entirely supplanted, a comfort perhaps to those of us who still thrill to the smell of a library.

But the dance through time between old brains and new ones, parents and children, tradition and innovation, is itself a deep part of human nature, perhaps the deepest part. It has its tragic side. Orpheus watched the beloved dead slide irretrievably into the past. We parents have to watch our children glide irretrievably into a future we can never reach ourselves. But, surely, in the end, the story of the reading, learning, hyperlinking, endlessly rewiring brain is more hopeful than sad.

Put these two together, and you get a picture that’s even more hopeful. Our brains aren’t just plastic over the span of human evolution or historical epochs, but over individual lives. It might be easier and feel more natural for children, whose brains seem to us to be nothing but plasticity. But we don’t just have a long childhood — to a certain extent, our childhood never ends.

Human beings are among the only species on the planet who evolved to thrive in any kind of climate and terrain on the planet. (Seriously; underwater is the only real exception.) Compared to that, summoning the plasticity required to engage with any new kind of media is a piece of cake.

In the darkness / Tim

Darkness at night is such an obvious and easily-neglected thing, probably because it’s no longer a problem. Our cities, even our houses, are made safe and accessible by electric light (and before that, gas lamps, candles, etc.).

But remember your experience of night as a child, the confounding absoluteness of darkness, and you begin to understand a fraction of what night was like prior to modern conveniences. The conquering of night might be the greatest event that wasn’t one in human history, certainly of the past 200 years — right up there with the massive declines in infant/mother death in childbirth or the emergence of professional sports.

Geoff Managh at BLDGBLOG lays it down with a tidy piece of paleoblogging by proxy:

Writing about the human experience of night before electricity, A. Roger Ekirch points out that almost all internal architectural environments took on a murky, otherworldy lack of detail after the sun had gone down. It was not uncommon to find oneself in a room that was both spatially unfamiliar and even possibly dangerous; to avoid damage to physical property as well as personal injury to oneself, several easy techniques of architectural self-location would be required.

Citing Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s book Émile, Ekirch suggests that echolocation was one of the best methods: a portable, sonic tool for finding your way through unfamiliar towns or buildings. And it could all be as simple as clapping. From Émile: “You will perceive by the resonance of the place whether the area is large or small, whether you are in the middle or in a corner.” You could then move about that space with a knowledge, however vague, of your surroundings, avoiding the painful edge where space gives way to object. And if you get lost, you can simply clap again.

Managh also thrills at Ekirch’s other discovery: “Entire, community-wide children’s games were also devised so that everyone growing up in a village could become intimately familiar with the local landscape.” Not only would you know your house in the dark, you would learn to know the architecture of your entire town. Managh asks:

But this idea, so incredibly basic, that children’s games could actually function as pedagogic tools—immersive geographic lessons—so that kids might learn how to prepare for the coming night, is an amazing one, and I have to wonder what games today might serve a similar function. Earthquake-preparedness drills?

Having spent most of the morning singing songs like “clean it up, clean it up, pick up the trash now” and “It’s more fun to share, it’s more fun to share,” I don’t see kids’ games as pedagogic tools as such a leap, although the collectivity of the game and the bleakness of the intent give me a chill. “If the French come to try to burn this village at night, the children must know exactly where they are before they begin to run.” Cold-blooded! They probably all learned songs about how kitchen knives and pitchforks could be used against an enemy, too. “Every tool can kill, every tool can kill…”

It’s probably also a good idea, if you’ve got kids, to teach them a thing or two about their neighborhoods. Not to get all grumpy and old, but in the absence of the random-packs-of-children-roaming-the-town-alone parenting style I grew up with, kids are probably not picking up the landmarks by osmosis. What will they do when the zombies attack? Use GPS? Call a cab?

Brought to you By the Committee to Find and Rescue Alma / matt

Apparently this short film by Pixar animator Rodrigo Blaas is only available for a limited time. Which is good, because otherwise an unlimited number of children would have their nightmares haunted forever.