Snark by Snark er … ONAmarket / matt

As the official Snarkmarket liveblogger, I’m always on the lookout for good stuff to liveblog. This morning’s event is the intro panel for the Online News Association conference in DC.

A family resemblance of obsessions / Tim

At HiLobrow, Matthew Battles interviews Tim Maly about his 50 Cyborgs project, for which Robin and I both wrote posts. Tim (Tim M, the other Tim) has a lot of nice things to say about Snarkmarket, and the whole interview is in part a response to Robin’s call for a postmortem on the project, but the interview’s mostly interesting for the smart things Tim says in response to Matt’s smart proddings.

***

A fair amount of the discussion circles around the nature of language. Here’s a representative chunk, where Matthew asks Tim about whether or not nonfiction criticism needs (or already has) a “fanfic impulse”:

I’m thinking about how Bruce Sterling in particular has identified or refined a series of concepts—spime, atemporality, favela chic, design fiction, to name a few — which people who aren’t students of his, but fans of his critique, sort of take up and extend. Maybe “hilobrow” has pretensions to this kind of conceptul life; “bookfuturism,” too has fans, now, and a life of its own. Of course we’re always doing this sort of thing in public discourse; it’s just a notion I have now that “fandom” becomes another mode or style of relating, alongside classroom, chiefdoms/tribes, and mentorship, among other models. Call it “fancrit”? Or not…

Tim is game, and runs with the “fancrit” idea:

The interesting thing about this, I think, is that where fanfic is necessarily ghettoized (you are playing with someone else’s copyrighted characters and worlds) fancrit is fed by a long academic tradition of fighting for mindshare via vocabulary. Sterling coins spime and that’s a meaningful event only to the extent that he can lose control of it. He wins when people start using the word without bothering to attribute it to him. Clynes & Kline coin cyborg and they end up winning to the point where Clynes becomes irritated with the way the meaning shifts and is twisted.

If you don’t get that etymological/genealogical twisting of cyborg from Clynes and Kline’s original, limited meaning, you don’t get 50 posts about it; the term itself isn’t generative or potent enough to move beyond its first-generation instance. It’s a concept that can’t conceive, in the sexual/reproductive sense.

***

That’s the power of language, which can be a dangerous power — it’s always exceeding our ability to, Humpty-Dumpty like, determine once and for all what words mean.

But it also means that words can be put into motion without permission, without determination — that they can circulate without anyone needing to hold them fast, or play Pope to decide what’s in and what’s out. They have a life of their own.

This is what I also like in Bruce Sterling’s comment on TM and MB’s conversation:

Some remarkable stuff in this discussion about positioning for niche intelligentsia eyeballs in the modern post-blogosphere. I think people used to call that activity “publishing,” but nowadays it’s a creolized effort badly in need of a neologism.

We don’t have a word for this! Let’s make one up! We have an old word, but it doesn’t work any more; it doesn’t mean what it should, or it means too much. Let’s let it go! Let it mean something else — and we can all talk about this in a different way.

***

I have something that I’m fond of saying, and it’s totally drawn from my training in philosophy: sometimes the most important thing you can do in an argument is to point out that we don’t have to talk about it the way we’ve always talked about it.

If you asked me to boil down the “real meaning” of the Bookfuturist manifesto I wrote, I’d say it’s that. We almost always talk about the relationship between culture and technology in very predictable ways that don’t solve problems. So let’s not talk about them that way anymore.

If you want a better example, look at this post on education, pointed to me by Rob Greco:

The “problems” we face with schools are right now are less about the schools themselves and more about a lack of vision and a fear of change. Put simply, the age-grouped, subject-delineated, 8 am-2 pm, September-June, one-size-fits-all system that we have makes the process of education easy. The realities of personal, self-directed, real problem-solving learning in a connected world are anything but.

Still, the hardest reality right now is that there is no groundswell to do school differently, not just “better.” Seems it’s easy to see a path to “better.” “Different” is just too scary.

***

If you want to do philosophy, or to show someone what it means to do philosophy, even your grandma, or a seven-year-old, get a group of people into a room and ask them, “what is a sport?”

Quickly, you’ll get strong opinions. Some people don’t think golf is a sport; other people don’t think figure skating should be one. Is dodgeball a sport? What about “tag”? (Some people are really good at tag.) Table tennis? Video games? Cheerleading? If not, why not? Eventually, people will try to come up with definitions. The definitions will resolve some problems but inevitably, they’ll exclude something that everyone in the room agrees is at least a borderline case.

What’s great about it is that you’re not arguing about the fundamental nature of the universe, drawing on complex symbolic logic, or questioning people’s ethical or religious beliefs (you know, depending on how strongly they feel about baseball).

You haven’t assigned any reading. There’s no mathematical equation to be solved, reference work to consult, or tool to be used to solve the problem. But everyone agrees that you’re talking about a real thing, something that actually exists and is relatively important, and at least for most of us, worth having an opinion about.

All you’re doing is asking everyone in the room to ask themselves: when I use such-and-such a word, what do I mean? What am I assuming? What am I committing myself to? If there’s a dispute between two people about how to use a word or what it means, how do we resolve it? How do we decide with language how we use language? And how do we do this, for the most part, completely organically and without great complication?

It’s a wonder. And it deserves to be wondered at.

***

Tim Maly has a great phrase for the group he gathered to work on 50 Cyborgs:

I’m lucky to have this great community (clique?) that’s emerged around a bunch of people whose work I love who have a family resemblance of obsessions.

“Family-resemblance,” if you don’t know, is an important phrase in philosophy. It’s the phrase Ludwig Wittgenstein uses to describe just the process I described above — how words like “game,” “sport,” “cyborg,” “community,” “book,” or “publishing” don’t have a single fixed meaning, a picture of a thing that you can match to each word, like God’s own dictionary.

Instead we’ve got this sloppy, fleshy language that generates and regenerates itself over time and across space and forms new clusters and meanings, and we can’t even collect the entire extension of the concept; all we can say is this word is used in such-and-such-a-way, and, within the broad unspoken assumptions of the lifeworld of a particularly community, we know what we mean and we know how to resolve misunderstandings.

Blogs — the best blogs — are public diaries of preoccupations. The reason why they are preoccupations is that you need someone who is continually pushing on the language to regenerate itself. The reason why they are public is so that those generations and regenerations and degenerations can find their kin, across space, across fame, across the likelihood of a connection, and even across time itself, to be rejoined and reclustered together.

Because that is how language and language-users are reborn; that is how the system, both artificial and natural, loops backward upon and maintains itself; because that is how a public and republic are made, how a man can be a media cyborg, and also become a city. That’s how this place where we gather becomes home.

All the pieces matter: Monopoly and The Wire / Tim

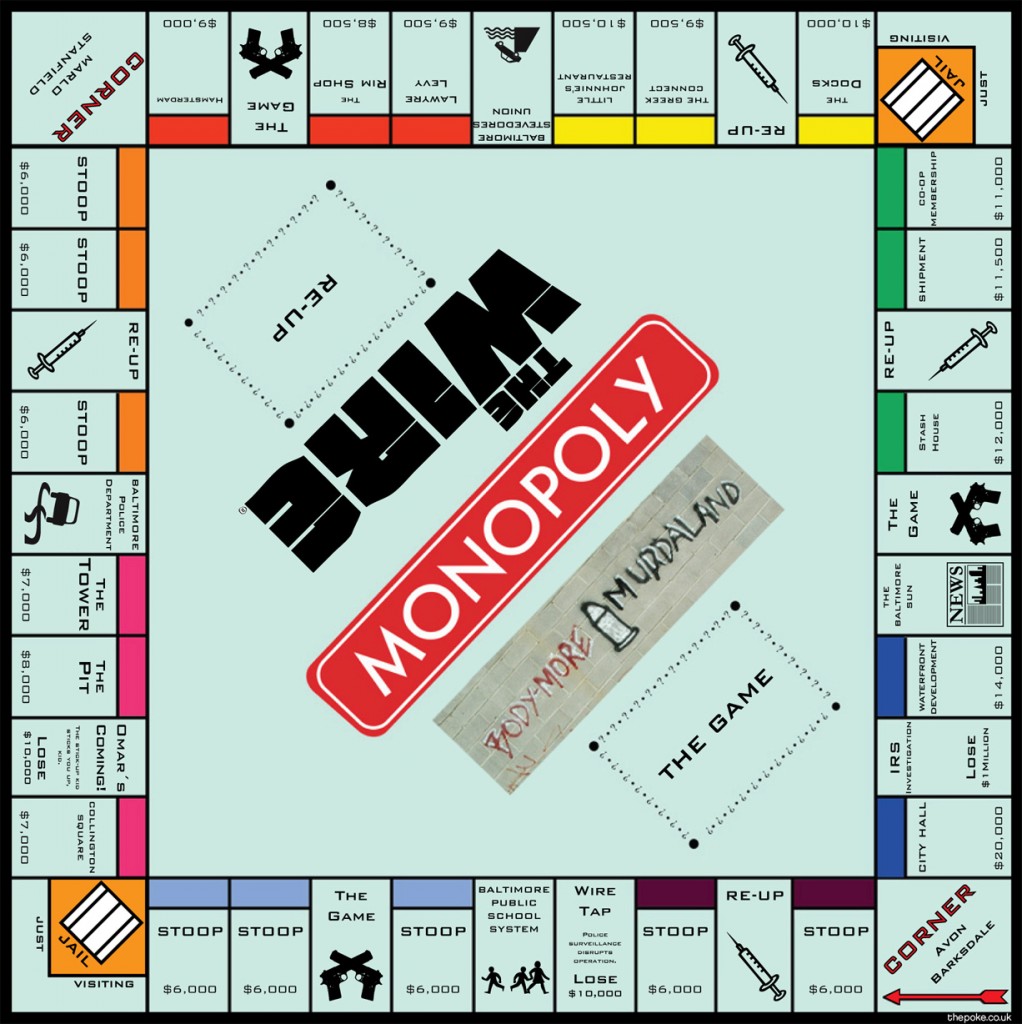

The Poke is a UK satirical site, a little bit like Chicago’s The Onion. Thursday, they published a fake news article about a version of Monopoly — complete with a fully-imagined and -illustrated fake gameboard — branded on the beloved HBO series The Wire:

“The Wire is all about corners,” says Hasbro spokesperson Jane McDougall, “and the Monopoly board is all about corners. It was a natural fit.” Based around the journey a young gangster might take through the fictionalised Baltimore of the show, players move from corner to stoop, past institutions featured in successive series like the school system and the stevedores union, acquiring real estate, money and power before ending up at the waterfront developments and City Hall itself.

There’s a classic scene in the first season of The Wire where D’Angelo (nephew of the drug boss Avon Barksdale and one of the series’s many unlikely protagonists) tries to teach two young dealers who work for him (Bodie and Wallace) how to play chess. Chess quickly turns into an elaborate metaphor to describe the violent realities and unreal ideals of the drug world they all live in:

But of course, it turns out not just to describe the drug world, but any world seen through the lens of The Wire. The two sides of the chess board could be one drug gang warring against another — Avon vs Marlo Stansfield. It could be the police detail trying to catch and trap the leader of one of the gangs. In the world of the police, too, pawns are expendable, and the people at the top fall under a completely different logic. (Every so often, a pawn will be transformed — like Prez, the hapless street cop who becomes first an invaluable decoder and data-miner and eventually, a middle school math teacher.)

But the single-plane, A vs B world of chess is really only an adequate metaphor for the narrow world of The Wire‘s first season, the immediate objectives that eventually get unravelled. As Stringer Bell tries to tell his partner Avon, “there are games beyond the game.”

That’s the world Stringer tries to navigate. You begin with drugs, fighting for corners. Then you step back, build institutions – other people work for you. Eventually, you transcend the street level and become a power broker, directing traffic but never touching the street. Then you take your ill-gotten capital — your Monopoly money — and turn it into real capital, by investing in (get this) real estate, political connections, legitimate businesses. Stringer Bell’s dream is Michael Corleone’s dream (which was Joe Kennedy’s dream). Power into wealth and back into power again. But it’s all just business.

That’s where Monopoly comes in. Like chess, Monopoly is about controlling territory. Unlike chess, it’s not neofeudal combat, with handed-down traditions and ideologies of strategy and honor — the illusion that everything is perfectly under the player’s control, that all the pieces in the game are visible.

Monopoly is transparently about money and greed. It lays bare the multiple, adjacent worlds and the interlocking systems that tie them together. (In The Wire, the worlds adjacent to drugs and cops include the ports, politics, the schools, and the media.) You gain territory and choose how you build on it, but you also roll dice and overturn hidden cards that can send you in a completely different direction. It’s actually absurdly easy for players to cheat — especially if you let them control the bank. And every time you pass Go, the game — at least in part — starts over again.

The Wire is about a lot of things — the decline of the American city, the futility of the war on drugs, the corruption of our institutions. It’s also about the gap between our ideologies of how things ought to be as opposed to the way they actually are. “You want it to be one way,” drug kingpin Marlo tells a worn-out security guard who tries to stop him from shoplifting. “But it’s the other way.”

Overwhelmingly, that gap plays out in the field of work. The second season, about the blue-collar port workers, is transparently about work — but really, every season is about workers, bosses, money, promotions, recognition. The innovation of The Wire with respect to its representation of drug gangs and cops is to present them as the mundane, kind of screwed-up workplaces that they are.

And capitalism has always been screwed-up about work. On the one hand, we’ve got Weber: the Protestant idea that work has an ethical value, that everybody has a calling and that we prove ourselves through our success. On the other, we’ve got Marx: the only way the system works is by extracting value from its workers, and the more value it can extract for less investment, the better the people at the top make out. “Do more with less,” as the newspaper editor, mayor, and police bosses say over and over again.

I think this is how I finally came to terms with The Wire‘s last season, which added journalism to the mix. It’s about that disillusionment — the idea that the work of journalism has an intrinsic value, and the corruption of that through cost-cutting and self-serving behavior. And maybe that disillusionment is extra bitter for Simon, who couldn’t stand what capitalism did to his newspaper, his city, its employers, its politics. The gall is too thick.

Simon’s collaborator Ed Burns had a more reconciled view of it; he’d worked as a cop, as a teacher, then a screenwriter/producer, and seemed to find satisfaction in different parts of each of them. It’s Burns’s wisdom we get when Lester Freamon tells Jimmy McNulty — who (like Simon) unleashes his anger on anyone who tries to get between him and his work — “the job will not save you.”

A Wire-themed Monopoly board might have begun as a joke, but let me tell you, Hasbro: you definitely think about it. I posted the link on Twitter, and it was picked up by Kottke and then by Slate, who both attributed me. You wouldn’t believe the reaction people had to this. Just like the series itself, it struck a chord. Also, just think of all the quotes from the series you can use to talk trash while you play:

The Comedy Closer / Tim

Bill Murray is 60 years old today, which is a little bit unbelievable. The Beatles, Dylan, and The Stones can be in their 60s, and Woody Allen sometimes seems like he was ALWAYS in his 70s, but Bill Murray? 60? My parents aren’t even 60 yet, but Bill Murray is?

Maybe between movies, he gets in a spaceship that approaches the speed of light– so 60 earth years have passed, but he’s still really (let’s say) 48. He understands aging, all too well, because he’s seen it happen to the people around him at lightning speed, but he himself is only slowly, gently moving through middle age.

HiLobrow has a short but very fine appreciation, which makes me miss their daily HiLo Heroes birthday posts all the more. The erstwhile site only does occasional pieces averaging about one per week now. I’m guessing it’s because the editorial load was too large to bear.

I know the editors, but I haven’t actually asked them why; I know that from my own occasional entry-writer’s perspective, it seemed like way too much work. But golly-gosh, these are still some of my favorite things to read on the web.

Here are some of my favorite Bill Murray clips. Watching them, you see that Murray’s real genius may be in his ability to react to those around him with sanity AND lunacy; like Woody Allen at his peak, he’s George and Gracie rolled into one. He’s such a generous comedic actor, he makes even ciphers like Andie McDowell in Groundhog Day or Scarlett Johanssen in Lost In Translation look great. And because your attention’s still on him, you don’t even notice he’s doing it.

On Twitter, I compared him to baseball closer Mariano Rivera. Murray — maybe especially has he’s gotten older — is the relief pitcher who finishes every game/scene. He makes everybody look better; you’re always talking about him, but somebody else usually gets the win. The starters set the table, and he just kills you a half-dozen different ways. Fastball = punchline, change-up = muted expression, curveball = unexpected character transformation, and a devastating fluttery cut fastball that’s a mixture of all three.

MSU Commencement Speech: May 3, 2001 / Tim

In Twitter today — and I mean, like ten minutes ago — I got involved in a Twitter discussion with Matt Novak and Mat Honan about our memories of the Cold War. Matt was about six years old when it ended, Mat 17, I was 11, so we all had slightly different memories, but generally each recall the atmosphere of fear and dread we had then.

Mat Honan pointed out that 9/11/2001 hadn’t scared him the way it had many others because he’d grown up in the shadow of nuclear war. The spectacle of the destruction of whole cities, whole nations, is of a different order of magnitude than three-four unconventional attacks on American cities. It just is. Maybe the latter is actually more frightening, because it’s more concrete, in the same way that falling out of a roller coaster scares us more than dying of heart disease. The first one, you can see.

I remembered that I’d been thinking a lot about nuclear war in 2000-2001 — mostly how the threat had been gently fading for ten years, like a fingerprint on glass — and that I’d mentioned it in my very unusual commencement speech that I gave to Michigan State’s College of Arts & Letters in May 2001.

I’d already gotten my BA in Mathematics in the fall, and was finishing my second/dual degree in Philosophy, starting an MA program in Math that everyone knew I’d never finish. (Hey, they gave me a job teaching algebra that spring and that summer!)

I knew I wanted to be a professor, but didn’t know in what; I wrote some awful applications to philosophy programs in Berkeley, Princeton, and Chicago explaining that I was interested in Greek philosophy, Nietzsche, formal logic, and John Locke, which I’m sure pegged me as someone who had no idea what they wanted to do and no clear research program to pursue, and that was probably right. I was still waiting for the official rejection slip from Berkeley, trying to make up my mind whether I was going to split to Chicago for their consolation-prize Masters’ Program, stay in East Lansing and teach more math, or try to find real work.

Paul Gauguin, Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?

I was obsessed with T.S. Eliot and Gauguin, respectively; I wanted to go to Boston that summer to find out more about each of them, but blew out a tire on the way and never made it. I’d already written my commencement speech though. Here it is.

(And before you ask, yes—this is total Sloan-bait for him to post HIS speech that he gave the next year to the BIG room at MSU, assuming he can find it on his hard drive.)

Kanye West, media cyborg / Robin

Tim Maly’s #50cyborgs project is unfolding this month, 50 years after the coining of the term “cyborg.” Here at Snarkmarket, our Tim has already contributed. Here’s my addition.

So, I love Tim Maly’s kickoff post: What’s a cyborg? It’s fun, revelatory, provocative, and it uses design to tell its tale. (You know I love that.) Tim laces the post with striking images, and he labels them: This is a cyborg. This is not a cyborg.

But I think he misses one.

Because this is a cyborg, too.

I’m not saying that because of the sampler on the pedestal or the vocoder attached to the microphone (although somebody could do a great #50cyborgs post about the recent robotization of pop vocals). I’m talking about the frame itself. About the image of a star on stage in front of 11 million people. About the digital distribution of that image to screens and eyeballs around the planet. And, most importantly, about the fact that Kanye West has the media muscles to make that happen.

Isn’t there such a thing as a media cyborg?

After you read Tim’s post, you start to see cyborgs all around you. It’s not just people with, you know, gun-legs; it’s anybody who uses a cell phone or wears contact lenses. It’s anybody who brings a tool really close in order to augment some capability.

Aren’t there people who have brought media that close? Aren’t there people who manipulate it, in all its forms, as naturally as another person might make a phone call, or speak, or breathe?

When you think of someone like Kanye West or Lady Gaga, you can’t think only of their brains and bodies. Lady Gaga in a simple dress on a tiny stage in a no-name club in Des Moines is—simply put—not Lady Gaga. Kanye West in jeans at a Starbucks is not Kanye West.

To understand people like that—and, increasingly, to understand people like us (eep!)—you’ve got to look instead at the sum of their brains, their bodies, the media they create, and the media created by others about them. All together, it constitutes a sort of fuzzy cloud that’s much, much bigger than a person.

This hits close to home for me. In fact, it’s the reason I do a lot of the things that I do. At some point in your life, you meet a critical mass of smart, fun, interesting people, and a depressing realization hits: There are too many. You’ll never meet all the people that you ought to meet. You’ll never have all the conversations that you ought to have. There’s simply not enough time.

You know those movie scenes where two characters miss each other by just a fraction of a second, and how it’s so frustrating to watch? You want to reach into the screen and go: Hey, stop! Just slow down. He’s coming around the corner! Well, that’s life—except in life, it’s multiplied a million-fold in every dimension. You can miss somebody not just by a second, but by a century. You can miss somebody not just by a couple of steps, but by the span of a continent.

Media evens the odds.

Media lets you clone pieces of yourself and send them out into the world to have conversations on your behalf. Even while you’re sleeping, your media —your books, your blog posts, your tweets—it’s on the march. It’s out there trying to making connections. Mostly it’s failing, but that’s okay: these days, copies are cheap. We’re all Jamie Madrox now.

Okay, let’s keep things in perspective. For most of us, even the blogotronic twitternauts of the Snarkmatrix, this platoon of posts is a relatively small part of who we are. But I’d argue that for an exceptional set of folks—the Kanyes, the Gagas, the Obamas—it is a crucial, even central, component.

Maybe that sounds dehumanizing, but I don’t think it ought to be. We’re already pretty sure that the mind is not a single coherent will but rather a crazy committee whose deliberations get smoothed out into the thing we call consciousness or identity or whatever. Use your imagination: what if some of that committee operates remotely? If 99.99% of the world will only ever encounter Kanye West through the bright arc of media that he produces—isn’t that media, in some important way, Kanye?

Again: I don’t think it’s dehumanizing. I don’t think it’s dystopian. Any cyborg technology has a grotesque extreme; there are glasses and there are contacts and there are these. So it’s like that with media, too. We all do this; we all use media every day to extend our senses and our spheres of influence. At some scale, sure, things gets weird, and you lose track of you, and suddenly you’re being choked to death by your own robotic arm. But way before you get to that point, you get these amazing powers:

- The power to reach beyond yourself, outward in space and forward in time.

- The power to have conversations—really rich, meaningful conversations—with more people than you could ever break bread with.

- And, increasingly, the power to get reports back from your little platoon—to see how your media is performing.

We’re all media cyborgs now.

P.S. Don’t miss Kevin Kelly’s contribution to #50cyborgs!

Paterson, or History of the Cyborg as City / Tim

Paterson is a long poem in four parts — that a man in himself is a city, beginning, seeking, achieving and concluding his life in ways which the various aspects of a city may embody — if imaginatively conceived — any city, all the details of which may be made to voice his most intimate convictions. Part One introduces the elemental character of the place. The Second Part comprises the modern replicas. Three will seek a language to make them vocal, and Four, the river below the falls, will be reminiscent of episodes — all that any one man may achieve in a lifetime.

— William Carlos Williams, “Author’s Note” to Paterson

[Note: This is one of 50 posts about cyborgs a project to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the coining of the term.]

[Note 2: This is also very literary, and very weird.]

William Carlos Williams knew plenty about bodies. He was a pediatrician and general practitioner in Rutherford, NJ, and his great poem “To Elsie,” which begins “The pure products of America / go crazy —” moves seamfully from the flesh to aimless machines:

voluptuous water

expressing with brokenbrain the truth about us–

her great

ungainly hips and flopping breastsaddressed to cheap

jewelry

and rich young men with fine eyesas if the earth under our feet

were

an excrement of some sky

…No one

to witness

and adjust, no one to drive the car

And then there is the mighty fragment from Spring and All, “The rose is obsolete,” imagining a new, cubo-futurist symbol of beauty with the delicacy and strength of organic steel. We could go on.

But Paterson is the poem, the book to be reckoned with, which conceives of a body as a city and a city as a body and both as a flow of heteroclite information, the poem a machine containing them all.

To make two bold statements: There’s nothing sentimental about a machine, and: A poem is a small (or large) machine made out of words. When I say there’s nothing sentimental about a poem, I mean that there can be no part that is redundant.

Prose may carry a load of ill-defined matter like a ship. But poetry is a machine which drives it, pruned to a perfect economy. As in all machines, its movement is intrinsic, undulant, a physical more than a literary character.

And this is what we see in Paterson. The italicized faux-definition on the first page in verso calls it “an identification and a plan for action to supplant a plan for action… a dispersal and a metamorphosis” but also “a gathering up; a celebration.” In other words, a book.

To make a start,

out of particulars,

and make them general, rolling

up the sum, by defective means–

Or as he would write (and repeat) a handful of pages later, “–Say it, no ideas but in things–” which is to say (he tries to refine) “no ideas but in facts” but also:

Say it! No ideas but in things. Mr.

Paterson has gone away

to rest and write. Inside the bus one sees

his thoughts sitting and standing. His

thoughts alight and scatter–

Paterson, whose ideas are themselves cities criss-crossing his streets in machines made from the mind, is both the Passaic Falls (“the outline of his back”) and the bridge thrown across those falls, and the men who dare each other to jump from the bridge, the women who mysteriously disappear, and finally the fragments of texts from newspapers and letters Williams gathers (the gathering at the same time a dispersal, a release of the information confined in the archive) to make the outline of his poem.

So far everything had gone smoothly. The pulley and ropes were securely fastened on each side of the chasm, and everything made in readiness to pull the clumsy bridge into position. It was a wooden structure boarded up on both sides, and a roof. It was about two o’clock in the afternoon and a large crowd had fathered — a large crowd for that time, as the town only numbered about four thousand — to watch the bridge placed in position.

That day was a great day for old Paterson. It being Saturday, the mills were shut down, so to give the people a chance to celebrate. Among those who came in for a good part of the celebration was Sam Patch, then a resident in Paterson, who was a boss over cotton spinners in one of the mills. He was my boss, and many a time he gave me a cuff over the ears.

Such prose fragments are dropped into the text of Paterson like stones in the Passaic Falls, or like Sam Patch’s body when, after a career of daredevil jumps inaugurated in Paterson (“a national hero”), it’s found frozen downstream after a jump from Niagara.

Sometimes the language is reincorporated later (or before) in the narrative (such as it is) of the poem. Williams describes Paterson as a search for language, the river like the language itself, many languages, bearing many kinds of information:

A false language. A true. A false language pouring— a

language (misunderstood) pouring (misinterpreted) without

dignity, without minister, crashing upon a stone ear.

And with this we are on the terrain of Claude Shannon’s mathematical cryptography, elaborated in the 1940s with the help of John von Neumann, Alan Turing, and others, just miles away, the engineering and metaphorical aspects of which fascinated Williams. In information theory, the medium of information is immaterial (both in the sense that is abstract and not relevant to the calculus), only its degree of distortion, compression, storage, and loss. Signals with(out) the codes to decipher them.

Once we can abstract from the medium, information does not need to be a letter, a photograph, or a radio wave. It can be a body, or the movement of bodies across a city, or any system, whether synthetic, organic, or hybrid.

Williams is known for his work as a physician, for his friendship with avant-garde artists, writers, and photographers in New York (the Williams-Marcel Duchamp-Man Ray friendship was especially fertile), but his interest in science and engineering was equally profound. In 1945, the year he forged Book One of Paterson, he received an honorary degree from the University of Buffalo, where he struck up a long conversation and fast friendship with Vannevar Bush, who that year would write “As We May Think“:

Among the rest the man Bush, the head of the atomic bomb project, was the most interesting to me. I liked him at once. It is amazing what he and his associates have accomplished—looked at simply as work, as brains. He seemed curious about me and was astonished to know I was a physician. I told him that I was deeply impressed by the sheer accomplishments of the persons on the platform. He replied that it took a lot of energy also to write books

(see T. Hugh Crawford, “Paterson, Memex, and Hypertext”)

How could we retrieve disconnected fragments, to make their hidden connections manifest? This was Williams’s problem as a poet, Bush’s as a researcher, Shannon’s as an engineer. To create a network of things — to roll up the universal out of particulars, and make what’s long kept in storage MOVE, faster than microfilm:

Our ineptitude in getting at the record is largely caused by the artificiality of systems of indexing. When data of any sort are placed, in storage, they are filed alphabetically or numerically, and information is found (when it is) by tracing it down from subclass to subclass. . . . Having found one item, moreover, one has to emerge from the system and re-enter on a new path

Or as Williams writes in Paterson:

Texts mount and complicate them-

selves, lead to further texts and those

to synopses, digests and emendations

A new line, for a new mind; a new mind, to be the mind of a city.

The library, the library is on fire by Book III of Paterson:

Hell’s fire. Fire. Sit your horny ass

down. What’s your game? Beat you

at your own game, Fire. Outlast you:

Poet Beats Fire at Its Own Game! The bottle!

the bottle! the bottle! the bottle! I

give you the bottle! What’s burning

now, Fire?The Library?

Whirling flames, leaping

from house to house, building to buildingcarried by the wind

the Library is in their path

Beautiful thing! aflame .

a defiance of authority

— burnt Sappho’s poems, burned

by intention (or are they still hid

in the Vatican crypts?) :

beauty is

a defiance of authority :for they were

unwrapped, fragment by fragment, from

outer mummy cases of papier mâché, inside

Egyptian sarcophagi .

Knowledge cannot lie dead, buried in tombs, it must be transmitted, brought to action, by electrical means if necessary, by film if necessary, fire if necessary, every destruction a liberation, bearing with it the possibility of rebirth.

That is, at least — if one conceives of the body as something more than flesh — as network — as city. As a machine made of words.

A machine with a man inside.

Snarkmarket Dispatches From Within Wired.com / Tim

Plenty of my posts at Wired.com’s Gadget Lab are pretty different from what I used to post, or even would want to post, here at Snarkmarket. (We don’t do a whole lot of product hands-on, industry news, or microprocessor specs, for example, here at Snarkmarket.)

Some of them, though, are totally SM-appropriate. Here’s a short list of posts that Snarkmarket readers might have missed in the past week that I think you’d love under any masthead:

- Tracing the Army Knife’s Swiss History

- E-Books Are Still Waiting for Their Avant-Garde

- How Google Instant Could Reinvent Channel Flipping

- Why You Should Get Excited About New Mobile Processors

- Games, Chat, ePub: Imagining the Future of Apps for Kindle

- Should You Give Up Gadgets for a Day? (NB: This one makes no sense, b/c editorial swapped out the photo of Mel Gibson that led it. It just reads like I’m weirdly obsessed with Mel Gibson,)

- The Hidden Link Between E-Readers and Sheep (It’s Not What You Think)

- Text-Free Computers Find Work for India’s Unlettered

Hope you enjoy! (And please, comment! We need an injection of Snarkmarket comment awesomeness at Wired badly. It’s a bad vibe over there.)

Constellation: The Internet ≅ Islam / Tim

I’ve reading semi-extensively (i.e., as much as I can without breaking down and buying any more books) about the history of Islam. I’m partly motivated by a desire to better understand its philosophy and manuscript traditions, partly for a half-dozen other reasons too complicated to explain, but mostly just from long-standing interest. A few of my Kottke posts came out of this, as Robin pointed out.

So the best article I’ve come across in a while that touches on all of these things is “What is the Koran?” which appeared in The Atlantic back in 1999. It’s an examination of scholarly debates over the historicity of the Koran, and the propriety of Western scholars applying empirical/rationalist techniques to a holy text (especially when, historically-speaking, Orientalism of this kind hasn’t been motivated by knowledge for knowledge’s sake), plus clampdowns on Muslim writers who’ve brought the traditional history into question.

(Brief summary: Mohammed didn’t write, but received revelations from God, which he recited and others memorized and/or wrote down. A while later, just as with Christianity, a council produced an officially sanctioned text, knocking out variant copies and apocryphal texts, some of which were… extremely interesting. So, let’s imagine the Gnostic Gospels coming out in a country ruled by fundamentalists.)

Anyways, part of the problem these scholars are struggling with is just how FAST Islam grew from outsider rebels to ruling establishment:

Not surprisingly, given the explosive expansion of early Islam and the passage of time between the religion’s birth and the first systematic documenting of its history, Muhammad’s world and the worlds of the historians who subsequently wrote about him were dramatically different. During Islam’s first century alone a provincial band of pagan desert tribesmen became the guardians of a vast international empire of institutional monotheism that teemed with unprecedented literary and scientific activity. Many contemporary historians argue that one cannot expect Islam’s stories about its own origins—particularly given the oral tradition of the early centuries—to have survived this tremendous social transformation intact. Nor can one expect a Muslim historian writing in ninth- or tenth-century Iraq to have discarded his social and intellectual background (and theological convictions) in order accurately to describe a deeply unfamiliar seventh-century Arabian context. R. Stephen Humphreys, writing in Islamic History: A Framework for Inquiry (1988), concisely summed up the issue that historians confront in studying early Islam.

If our goal is to comprehend the way in which Muslims of the late 2nd/8th and 3rd/9th centuries [Islamic calendar / Christian calendar] understood the origins of their society, then we are very well off indeed. But if our aim is to find out “what really happened,” in terms of reliably documented answers to modern questions about the earliest decades of Islamic society, then we are in trouble.

But one of the things that happened during this period is that Islam went from wild, oral, incomprehensible traditions to scholarly/poetic/cultural flowering to clamped-down authoritarian fundamentalism:

As Muslims increasingly came into contact with Christians during the eighth century, the wars of conquest were accompanied by theological polemics, in which Christians and others latched on to the confusing literary state of the Koran as proof of its human origins. Muslim scholars themselves were fastidiously cataloguing the problematic aspects of the Koran—unfamiliar vocabulary, seeming omissions of text, grammatical incongruities, deviant readings, and so on. A major theological debate in fact arose within Islam in the late eighth century, pitting those who believed in the Koran as the “uncreated” and eternal Word of God against those who believed in it as created in time, like anything that isn’t God himself. Under the Caliph al-Ma’mun (813-833) this latter view briefly became orthodox doctrine. It was supported by several schools of thought, including an influential one known as Mu’tazilism, that developed a complex theology based partly on a metaphorical rather than simply literal understanding of the Koran.

By the end of the tenth century the influence of the Mu’tazili school had waned, for complicated political reasons, and the official doctrine had become that of i’jaz, or the “inimitability” of the Koran. (As a result, the Koran has traditionally not been translated by Muslims for non-Arabic-speaking Muslims. Instead it is read and recited in the original by Muslims worldwide, the majority of whom do not speak Arabic. The translations that do exist are considered to be nothing more than scriptural aids and paraphrases.) The adoption of the doctrine of inimitability was a major turning point in Islamic history, and from the tenth century to this day the mainstream Muslim understanding of the Koran as the literal and uncreated Word of God has remained constant.

Okay. Now let’s read The Economist, “The future of the internet: A virtual counter-revolution“:

THE first internet boom, a decade and a half ago, resembled a religious movement. Omnipresent cyber-gurus, often framed by colourful PowerPoint presentations reminiscent of stained glass, prophesied a digital paradise in which not only would commerce be frictionless and growth exponential, but democracy would be direct and the nation-state would no longer exist…

Fifteen years after its first manifestation as a global, unifying network, it has entered its second phase: it appears to be balkanising, torn apart by three separate, but related forces…. It is still too early to say that the internet has fragmented into “internets”, but there is a danger that it may splinter along geographical and commercial boundaries… To grasp why the internet might unravel, it is necessary to understand how, in the words of Mr Werbach, “it pulled itself together” in the first place. Even today, this seems like something of a miracle…

One reason may be that the rapid rise of the internet, originally an obscure academic network funded by America’s Department of Defence, took everyone by surprise. “The internet was able to develop quietly and organically for years before it became widely known,” writes Jonathan Zittrain, a professor at Harvard University, in his 2008 book, “The Future of the Internet—And How To Stop It”. In other words, had telecoms firms, for instance, suspected how big it would become, they might have tried earlier to change its rules.

Maybe this is a much more common pattern than we might realize; things start out radical and unpredictable, resolve into a productive, self-generating force, then stagnate and become fixed or die. Boil it down, and it sounds fairly typical. That how stars work, that’s how cities work, maybe that’s just how life works.

But in both articles, Islam and the Internet are presented as outliers. Judaism and Christianity didn’t grow as fast as Islam did, and their textual tradition produces similar problems, but don’t appear to be as sharp. Likewise, information networks like railroads, the telegraph, and telephone are presented as normally-developing; the internet is weird. Either this pattern is more common than we think it is, or it isn’t. Either way, it’s a meaningful congruence.

If that’s the case — if we can use the history of Islam to think about the internet, and vice versa, then what are the lessons? What are the porential consequences? What interventions, if necessary, are possible? (We have to confront the possibility in both cases that any intervention might be ruinous.)