I played a funny litcrit game with a very serious journalism debate. I started drawing lines and rectangles and filling in blanks. It’s a little like highbrow madlibs. And it helped me figure a few things out.

Short summary: the debate between Glenn Greenwald and Bill Keller in the pages of the NYT articulates a lot of the big ideas people inside and outside the profession have had about the practice of journalism. (Also, about the relative merit of David Brooks, but that’s a sideline.)

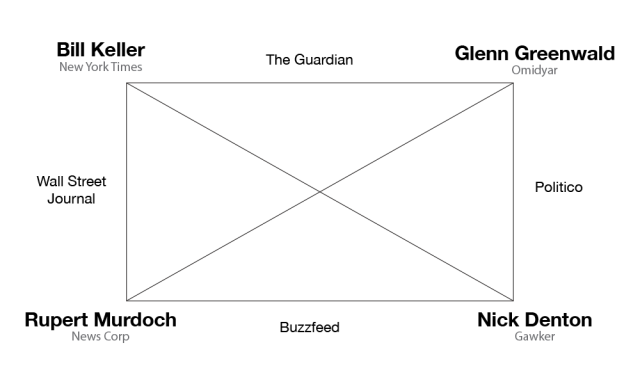

But by framing it as a back and forth between two poles, it leaves a lot out. It actually doesn’t really recognize how close Greenwald and Keller really are in their basic assumptions about what kind of journalism is important and why, in their faith in the truth and in reader’s abilities to sort out really hard questions for themselves. And they’re arguing with each other, but also past each other, to targets they can’t quite bring themselves to name: people like Rupert Murdoch, and Nick Denton.

The left side is corporate or traditional media; the right is online media. The top is “serious” journalism; the bottom is tabloid journalism. For Keller and Greenwald, journalism is a calling; for Murdoch and Denton, it is a business. And without the largesse of patrons committed to the same ideals of journalism, the New York Times and Greenwald’s untitled venture with Omidyar would be very paltry businesses indeed, while Denton’s and Murdoch’s flourish, grow, and evolve. The New York Times, Washington Post, Guardian, and Pro Publica, and a few others, have found a space in which they can continue to exist. But it seems to me foolish to deny that for everyone else, the business models and journalistic practices mapped by Murdoch and Denton are proving to be much more robust, repeatable, and influential.

The picture up top is called a semiotic square, and it’s a way of representing a few basic principles:

- Most attempts to think through things rest on an opposition between two ideas;

- When you pick those two, you’re usually suppressing two other oppositions;

- You’re also usually suppressing some kind of excluded middle or reconciliation between opposed terms.

This has always felt very logical to me. Maybe it’s because it’s like a math problem. If we say, “ok, there are two kinds of numbers, whole numbers and fractions” — well, you’re forgetting about the things that are neither of those. And that’s actually MOST of the numbers. So we say, okay, there are whole numbers and fractions, and not-whole numbers, and not-fractions (irrationals). But wait — now we’re just talking about REAL numbers, and if we’re interested in NUMBERS, you’ve got to talk about imaginary numbers too. And not just imaginary but complex.

And so on. You can always, always, ALWAYS, go further down by expanding and relaxing your field of assumptions. And you can do it all with a pen and a piece of paper. (For reasons I don’t fully understand, this has always been really important for all the fields I’ve been drawn too intellectually — the only tools you need to carry them out are books, pen, and paper. Maybe a calculator, ruler and compass, and a camera.)

But because I know you can always go further down, I know that this graph of journalism is really incomplete. It’s a schema — it clarifies some things, but it obscures even more. And it makes things fixed that are really on the move. It’s like those beads-and-wire atomic models we made of elements in middle school — shit, electrons just aren’t moving around in quiet circles like that. Electrons are a MESS.

So I’d really like to get some pushback and extensions on this here. Jay Rosen was kind enough on Twitter to say that I didn’t pay enough attention to the debate over insiders vs outsiders, access vs accountability, in contemporary journalism. I talk about it a little bit in terms of complicity with the mechanisms of power. But how extensible is that to finance journalism, sports, entertainment, technology? Maybe it is, or maybe we need to blend that discussion with one of access.

And that points to another limitation: even the graph I made sort of takes investigative political journalism as being the field of discourse. And news, journalism, media is enormous! And the centrality of political accountability journalism is not at all self-evident.

Does Silicon Valley care about this shit? Does Wall Street? Does the science blogosphere? Does ESPN? Kinda. But not really. For them the field of action, of real power, of news of genuine importance, is elsewhere. It intersects with that world of electoral politics and state power, but only tangentially and accidentally.

And where do data and coding fit in? Nothing in this graph tells me whether I should learn to code, or what “learning to code” means. Which as we all know, is the most important question for journalism in human history. I mean, if I knew how to program in R, this sad-ass square could be a super-slick data visualization with crazy mouseovers and tilt-shift views and shit.

So what do you all think? If this is a place to start, how can we make it better?