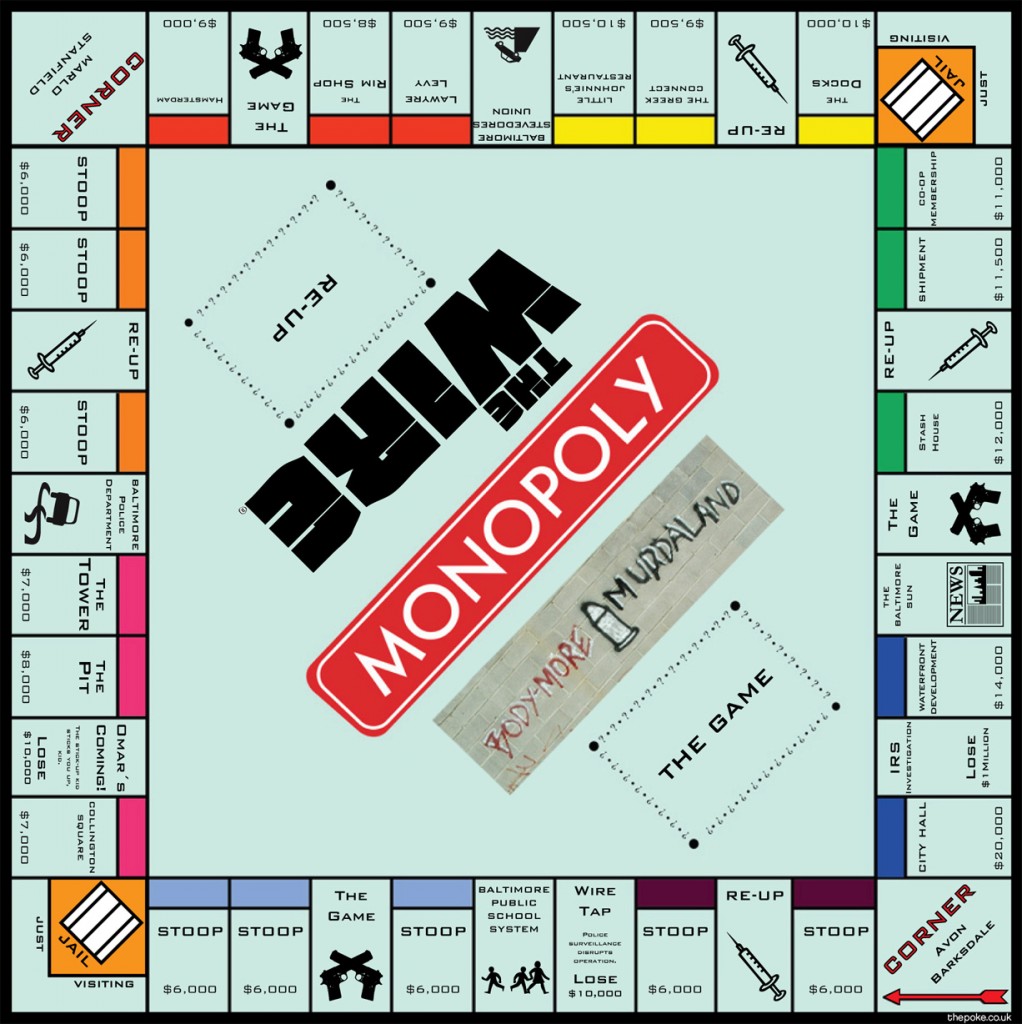

The Poke is a UK satirical site, a little bit like Chicago’s The Onion. Thursday, they published a fake news article about a version of Monopoly — complete with a fully-imagined and -illustrated fake gameboard — branded on the beloved HBO series The Wire:

“The Wire is all about corners,” says Hasbro spokesperson Jane McDougall, “and the Monopoly board is all about corners. It was a natural fit.” Based around the journey a young gangster might take through the fictionalised Baltimore of the show, players move from corner to stoop, past institutions featured in successive series like the school system and the stevedores union, acquiring real estate, money and power before ending up at the waterfront developments and City Hall itself.

There’s a classic scene in the first season of The Wire where D’Angelo (nephew of the drug boss Avon Barksdale and one of the series’s many unlikely protagonists) tries to teach two young dealers who work for him (Bodie and Wallace) how to play chess. Chess quickly turns into an elaborate metaphor to describe the violent realities and unreal ideals of the drug world they all live in:

But of course, it turns out not just to describe the drug world, but any world seen through the lens of The Wire. The two sides of the chess board could be one drug gang warring against another — Avon vs Marlo Stansfield. It could be the police detail trying to catch and trap the leader of one of the gangs. In the world of the police, too, pawns are expendable, and the people at the top fall under a completely different logic. (Every so often, a pawn will be transformed — like Prez, the hapless street cop who becomes first an invaluable decoder and data-miner and eventually, a middle school math teacher.)

But the single-plane, A vs B world of chess is really only an adequate metaphor for the narrow world of The Wire‘s first season, the immediate objectives that eventually get unravelled. As Stringer Bell tries to tell his partner Avon, “there are games beyond the game.”

That’s the world Stringer tries to navigate. You begin with drugs, fighting for corners. Then you step back, build institutions – other people work for you. Eventually, you transcend the street level and become a power broker, directing traffic but never touching the street. Then you take your ill-gotten capital — your Monopoly money — and turn it into real capital, by investing in (get this) real estate, political connections, legitimate businesses. Stringer Bell’s dream is Michael Corleone’s dream (which was Joe Kennedy’s dream). Power into wealth and back into power again. But it’s all just business.

That’s where Monopoly comes in. Like chess, Monopoly is about controlling territory. Unlike chess, it’s not neofeudal combat, with handed-down traditions and ideologies of strategy and honor — the illusion that everything is perfectly under the player’s control, that all the pieces in the game are visible.

Monopoly is transparently about money and greed. It lays bare the multiple, adjacent worlds and the interlocking systems that tie them together. (In The Wire, the worlds adjacent to drugs and cops include the ports, politics, the schools, and the media.) You gain territory and choose how you build on it, but you also roll dice and overturn hidden cards that can send you in a completely different direction. It’s actually absurdly easy for players to cheat — especially if you let them control the bank. And every time you pass Go, the game — at least in part — starts over again.

The Wire is about a lot of things — the decline of the American city, the futility of the war on drugs, the corruption of our institutions. It’s also about the gap between our ideologies of how things ought to be as opposed to the way they actually are. “You want it to be one way,” drug kingpin Marlo tells a worn-out security guard who tries to stop him from shoplifting. “But it’s the other way.”

Overwhelmingly, that gap plays out in the field of work. The second season, about the blue-collar port workers, is transparently about work — but really, every season is about workers, bosses, money, promotions, recognition. The innovation of The Wire with respect to its representation of drug gangs and cops is to present them as the mundane, kind of screwed-up workplaces that they are.

And capitalism has always been screwed-up about work. On the one hand, we’ve got Weber: the Protestant idea that work has an ethical value, that everybody has a calling and that we prove ourselves through our success. On the other, we’ve got Marx: the only way the system works is by extracting value from its workers, and the more value it can extract for less investment, the better the people at the top make out. “Do more with less,” as the newspaper editor, mayor, and police bosses say over and over again.

I think this is how I finally came to terms with The Wire‘s last season, which added journalism to the mix. It’s about that disillusionment — the idea that the work of journalism has an intrinsic value, and the corruption of that through cost-cutting and self-serving behavior. And maybe that disillusionment is extra bitter for Simon, who couldn’t stand what capitalism did to his newspaper, his city, its employers, its politics. The gall is too thick.

Simon’s collaborator Ed Burns had a more reconciled view of it; he’d worked as a cop, as a teacher, then a screenwriter/producer, and seemed to find satisfaction in different parts of each of them. It’s Burns’s wisdom we get when Lester Freamon tells Jimmy McNulty — who (like Simon) unleashes his anger on anyone who tries to get between him and his work — “the job will not save you.”

A Wire-themed Monopoly board might have begun as a joke, but let me tell you, Hasbro: you definitely think about it. I posted the link on Twitter, and it was picked up by Kottke and then by Slate, who both attributed me. You wouldn’t believe the reaction people had to this. Just like the series itself, it struck a chord. Also, just think of all the quotes from the series you can use to talk trash while you play:

3 comments

Barksdale. Avon and D’Angelo Barksdale. Not Stansfield.

Yep. I get it right later. Sloppy.

Incidentally, later on Thursday I heard some of the MSU rhetoric & writing faculty talking about Monopoly: The Wire Edition. There was a general sense that yes, this would be worth owning and playing. Hasbro, this is your cue.